Hollywood Actors, Writers Enter Fifth Month of Strike

The filmmaking industry is in trouble. While Barbie and Oppenheimer have soared with their ticket sales, other movies are struggling at the box office. This year has had several high-budget box office bombs for studios, such as The Flash for Warner Bros., Fast X for Universal, Indiana Jones for Disney, and Mission Impossible 7 for Paramount. Studios like WB and Disney have also begun to cut down on original streaming content, as every major streaming surface that isn’t named Netflix has lost millions of dollars this year. Then most of Hollywood stopped working.

At the beginning of May, the Writer’s Guild of America (WGA), a union of television and film writers and showrunners, went on strike against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), the group of the major heads of studios like Warner Bros, NBCUniversal, Disney/Fox, and Paramount. In June, they were joined by SAG-AFTRA, the union of American actors for film and television. This work stoppage has delayed several anticipated projects and fan-favorite series, and with no end in sight, striking workers are starting to leave the industry so they can survive.

Strikes occur when a business has a labor union, which is a group of workers that unite together to ensure they have good working conditions. The business creates a contract of employment for employees, and every so often, they sit down with the union in negotiation over changes to the contract. If the workers get improved conditions and are satisfied, they keep working. If their conditions are not met by the new contract, the workers stop working and picket outside the business, leaving the business with no workers and preventing non-union workers (nicknamed scabs) from taking their place.

While union membership dipped in the ’80s, union activity has been on the rise in the wake of the pandemic. UPS drivers got a pay raise and air conditioning in their trucks thanks to their union earlier this summer, as did the pilot’s union at American Airlines. Not all union stories are success stories though: this year has seen both Starbucks and Amazon take drastic measures to prevent unionization.

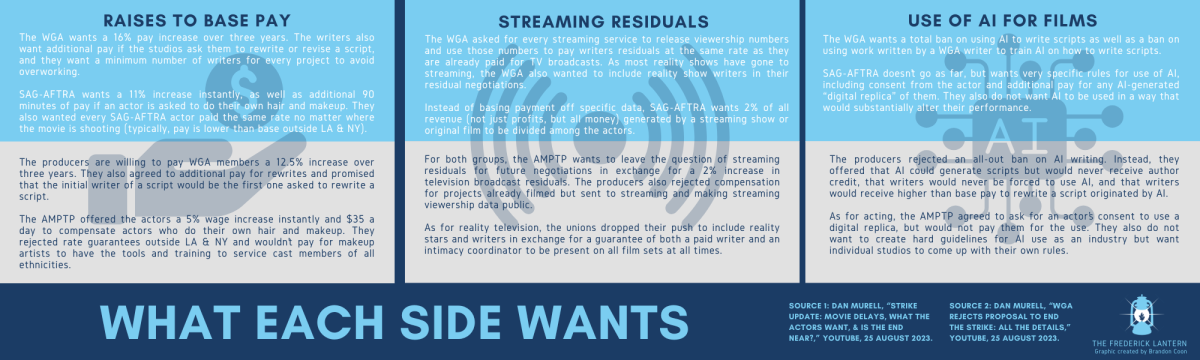

While the Hollywood Strike is really two strikes, both the WGA and SAG-AFTRA have the same three concerns that they want addressed: fair pay, streaming rights, and AI protection.

When it comes to pay, both the writers and the actors want an increase in the base level of pay to account for an increase in the cost of living (especially in Los Angeles). While A-list Hollywood actors and Emmy-award-winning writers can be paid millions for their work on a movie or television show, these pushes to increase base pay aren’t for them, as they negotiate every contract to work independently. The base pay increase is intended to help all the writers and actors of smaller films and shows, the ones who aren’t the big stars but still need to feed their families through their work.

“We’re not talking about us. We’re talking about so many people that haven’t been as lucky as we are,” actor Zach Braff said to the Washington Post. “I heard a stat recently that only 12 percent of SAG-AFTRA makes the $26,000 that’s the minimum to qualify for health insurance every year. So we’re here for people like that.”

Their second grievance, streaming rights, is a more difficult issue to explain. As part of their contract, writers and actors don’t just get paid for their initial on-set work–they also get paid for every time their film or series is purchased as a DVD or Blu-Ray or is broadcast on traditional television. These payments (called residuals) are usually a few cents for each instance, but they add up fast and are a major source of income for Hollywood actors and writers. Unfortunately, residual payments have been decreasing over the past few years as more people are dumping movie theatres, physical media, and cable TV for streaming. Thus, the actors and writers want to get residuals from streaming. Since (as previously mentioned) nearly every studio is losing money already with streaming, the AMPTP doesn’t want to give out streaming residuals.

Perhaps the biggest issue at hand is AI. With the debut of ChatGPT4 earlier this year, generative AI programs have been hailed as a game changer for society. Hollywood writers are worried that studios will replace writer’s rooms with AI writers as a cost-cutting measure, so they are asking for a minimum number of writers to be hired for all projects, that they work for a minimum amount of time, and that they actually be employed to write and not just rewrite scripts created by AI.

Actors are similarly worried about AI, as one studio leaked a plan to scan background actors into a computer and pay them once, then use their CG-generated image for any project they want in the future. Actors want absolute control over their own image and, if old footage is used to create a CG-generated version of themselves for a future movie, they get additional payment and the right to refuse participation. They also want guarantees that actual actors will be hired for all vocal work (like narration and animation) and that studios don’t just generate voices using AI.

Typically during a strike, both the union and the bosses meet every day in negotiations to try to come to an agreement on a new contract. These strikes have been different. After the WGA went on strike, they set several dates to resume negotiations, but the AMPTP didn’t show up for any of those meetings. When the two parties finally did meet on August 24, the AMPTP didn’t come to the table to bargain — instead, they gave the writers a non-negotiable final offer and leaked the contract to the media, which violated the rules of negotiations. The AMPTP is using similar tactics to ignore calls to negotiate from the actors union. After SAG-AFTRA agreed to delay striking until July 13 so they could extend negotiations, they were shocked to find that the AMPTP refused to negotiate and just wanted that extension so they could promote Barbie and Oppenheimer before their opening weekend.

In her public statement announcing the strike, SAG-AFTRA president Fran Drescher said, “I went in, in earnest, thinking that we would be able to avert a strike […] I am shocked by the way the people that we have been in business with are treating us. I cannot believe it, quite frankly, how far apart we are on so many things.”

Why is the AMPTP being so obstinant? It may be because the studios aren’t doing so well: representatives from the AMPTP have cited streaming losses and a slump in ticket sales as justifying their reluctance to increase wages and costs. Yet these same studio heads that bemoan the money they’re losing are extremely well paid: Disney/Fox CEO Bob Iger just signed a $27 million per year contract, while David Zazlav of Warner Discovery was paid $39.9 million to take over as CEO when the two companies merged last year.

This fact was not lost on Drescher in her strike announcement: “They [AMPTP] plead poverty, that they’re losing money left and right when giving hundreds of millions of dollars to their CEOs. It is disgusting […] We are the victims here. We are being victimized by a very greedy entity.”

Victimizing the strikers may be a big part of the producers’ plan. A July 11 report from Deadline went viral when they reported that a studio executive told them that “the endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses.” This tactic, while ruthless, may be working. Many actors and writers have had to stop paying for their health insurance and some are losing their homes.

“We’re all not Tom Cruise!” actor Danny Trejo told reporters. “Everything’s gone up but our wages […] We’ve got to support our money.” Actor Billy Porter made news when he lost his home because of the strike, while several other striking writers and actors have had to get jobs as dogwalkers, Uber drivers, and restaurant workers just to survive.

Despite all of this, neither the actors nor the writers are giving in. To help alleviate the financial issues of striking actors and writers, A-list celebrities like Dwayne Johnson, Leonardo DiCaprio, Oprah Winfrey, Hugh Jackman, Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively, Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, and Arnold Schwarzenegger donated $15 million of their own funds. Other major celebrities who are not hurting financially from the strike are using their notoriety to get the public on the side of the strikers.

“I’m striking because if it wasn’t for the folks who fought for me to have residuals, I would’ve been living on ramen for the rest of my life,” Ashoka star Rosario Dawson said from the picket lines. “I mean, I really am grateful for what we have, but the industry has changed and those contracts need to be updated as well.”

The only way a strike can end is if either both sides negotiate together or one side gives in. Neither side seems to be giving up, but most analysts think that the producers will come back to the negotiating table and give in to some demands to end the strike.

Part of this assumption is simple economics. Studios are losing money and streaming subscribers the longer the strike goes on. California productions have lost $3 billion from this strike already. Among the movies that have had to stop filming are Deadpool 3, Beetlejuice 2, the second part of Mission: Impossible: Dead Reckoning, and Venom 3.

Finished films are also being delayed: Dune: Part Two is getting delayed until next March because none of the striking actors will promote the movie while the strike is still ongoing. On the television side of things, late-night shows have been on hiatus since May and risk losing their entire audience while fall series are being delayed or, like the Chucky TV show, will air the few episodes that have been finished before going on hiatus.

While the studios can’t make any projects while the strike is ongoing, lots of actors and writers are still working. Since the WGA, SAG-AFTRA, and AMPTP are all American unions, productions outside America like House of the Dragon and Black Mirror are still in production. SAG-AFTRA and the WGA have also allowed their members to work at studios that are not part of AMPTP like A24, Neon, and STX International.

What may ultimately bring the AMPTP back to bargain isn’t that they don’t want to lose any more money– it may be that the actors and writers aren’t ever going to give in. Each union has called this moment an existential crisis for their industry, and they see their battle as one many industries will soon face with the changes that AI will bring to our society.

In her address calling for the strike, Drescher said that this strike affects “not only members of this union but people who work in other industries […] This is a moment of history. That is a moment of truth. If we don’t stand tall right now, we are all going to be in trouble. We are all going to be in jeopardy of being replaced by machines and big business who cares more about Wall Street than you and your family.”

It doesn’t hurt that actors and writers have the public on their side: a recent Gallup poll showed that 67 percent of Americans support the strikers and believe the studios are acting unfairly. Still, the best scenario for all parties would be for the strike to end and for everybody to get back to work, but that doesn’t look likely. With a full slate of winter movies ready to put into theatres, most industry pundits believe the strike will go on until next year.

But if the WGA and SAG-AFTRA are right, then the next big thing to come out of Hollywood won’t be a billion-dollar movie but a revolution in labor relations that will affect all businesses in the future.

-

2023-2024Timberwolves Defeat Nuggets, Ending Back-to-Back Hopes

-

2023-2024DWP: Driving While on a Phone

-

2023-2024Fit or Frustrating?

2023-2024Fit or Frustrating? -

2023-2024KAYA PALUDA: Balancing Body and Mind

2023-2024KAYA PALUDA: Balancing Body and Mind -

2023-2024Match Made in Heaven

2023-2024Match Made in Heaven -

2023-2024Mr. Dufour: A Frederick Legend Retires

2023-2024Mr. Dufour: A Frederick Legend Retires -

2023-2024Kendrick and Drake Fight, Everyone Loses

2023-2024Kendrick and Drake Fight, Everyone Loses -

2023-2024FAFSA Delays Push CU, CSU Enrollment

2023-2024FAFSA Delays Push CU, CSU Enrollment -

2023-2024Fallout Is Outstanding

2023-2024Fallout Is Outstanding -

2023-2024Abigail Is a Bloody Treat

2023-2024Abigail Is a Bloody Treat