Presidential inaugural speeches aren’t traditionally based around new policy, but Donald Trump is no stranger to breaking presidential tradition. In Monday’s address to the nation, he outlined several “day one” policies he intended to enact after his speech concluded. Among the policies that were the cornerstones of his campaign, like curtailing immigrant protections and the rights of LGBTQ+ Americans, one seemed to surprise those in attendance, Democrats and Republicans alike: Trump pledged to change the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America and revert the name of Denali to its previous moniker of Mt. McKinley.

This begs the question: are these the only two landmarks the Trump administration wants to rename? And if not, will the new administration revert some Coloradan landmarks back to their previous names? Of specific concern is Mt. Blue Sky, the state’s highest mountain that was renamed from Mt. Evans in 2023. While Trump is brash and unpredictable—qualities that his supporters love and his detractors loathe—there’s little likelihood his administration could or would even want to rename Mt. Blue Sky and other Colorado landmarks.

What’s in a Name?

To discuss how to change the names of mountains, gulfs, and other locations, it helps to know how they got their names in the first place.

Naming spots on the map is the job of the US Board on Geographic Names (BGN). The BGN is a federal board with members from the US Postal Service, the Library of Congress, CIA, and the Departments of Interior, State, Agriculture, Commerce, and Homeland Security. This committee approves all new names for places, though ultimately their decisions must be approved by Congress.

Since 1947, the BGN has been responsible for making sure the names of geographic places are uniform throughout the US. If Georgia says its capitol city is Atlanta, then every other state has to refer to that city as Atlanta and not Marthasville (which was its name prior to 1847). The BGN even standardizes how Americans and American maps refer to places in other countries. For example, they changed the spelling of Turkey to Türkiye on world maps printed in the US in 2023. The BGN also standardizes the official American names for oceaniac landmarks, Antarctic regions, and mapped areas of space.

When the BGN was founded by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890 as an advisory board, most of the eastern US was well mapped while the western US was rife with inconsistencies and places lacking known names. In deciding the name for a place, the BGN goes local: the board asks residents what they call a town, mountain, river, or other feature that could find itself on a map. Despite an effort to be historically consistent, this led to a lot of US place names being chosen by the first person or group to get their name recorded by the BGN.

Denali, Blue Sky, and the Push for New Names

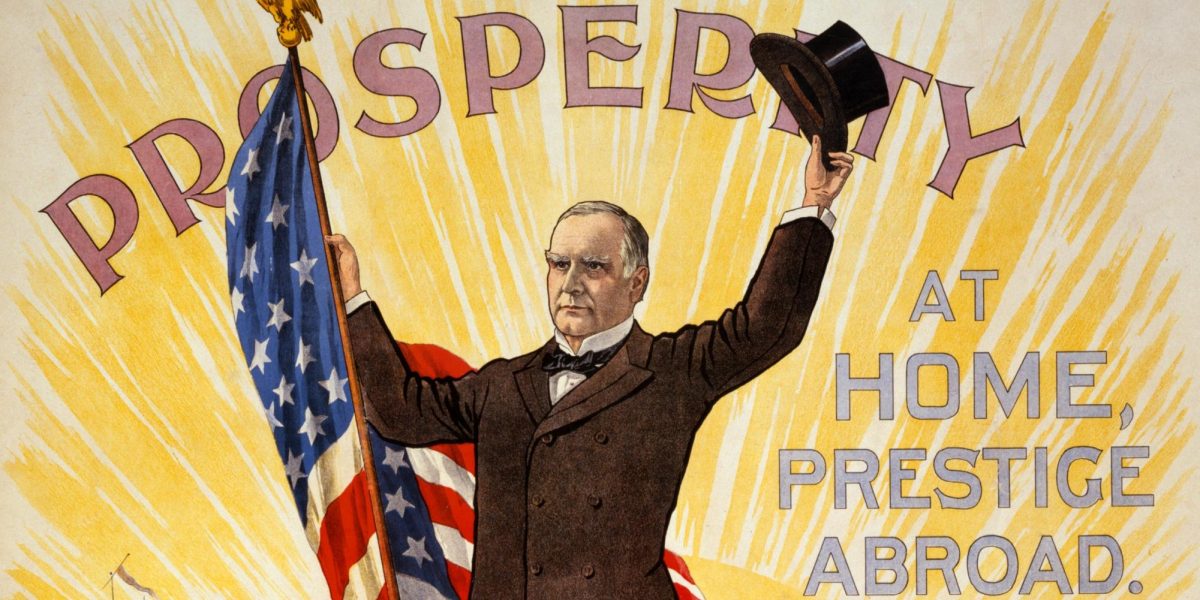

This was the exact scenario behind the name Mt. McKinley. The Athabaskan-speaking indiginous tribes of Alaska called the country’s tallest mountain Denali (“the great one”) for centuries. A prospector named William Dickey first called the peak “Mt. McKinley” in an 1896 article published in the New York Sun. At the time, McKinley was running for president to support the gold standard. Dickey liked this, as McKinleys’ policies would keep gold prices high. The moniker Mt. McKinley stuck after the Ohio Republican was elected and subsequently assassinated.

The name of the mountain was always a point of contention until 2015. The Obama administration changed the official name of the mountain to Denali after petitions from native tribes and Alaska’s senators. The announcement of the name change noted that McKinley had never been to Alaska, so the locals felt no affection for the Americanized name.

This started a trend toward renaming places in the US after their indiginous appellations instead of names picked by white colonizers. This was a reversal of how place names were originally chosen, where names were often picked in honor of settlers or famous Americans.

Colorado joined this trend in 2023 after a 2019 petition from the Colroado Geographic Naming Advisory Board (the state’s version of the BGN) approved Mt. Evans’ rename to Mt. Blue Sky. The previous name of the fourteener honored Territorial Governor John Evans, a controversial figure even in his own time. Evans helped plan and execute efforts to murder and relocate Colorado’s indiginous population. Evans’ schemes included the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, an event so horrific that it led Evans to resign as governor.

Several other places in Colorado received new names a year prior to Mt. Blue Sky as part of Secretary Order 4304. Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior under President Joe Biden, ordered that all US place names containing the word “squaw” must receive a new name. Congress identified sq— as a slur against indiginous women, and recent rules governing the BGN don’t allow place names to be derrogatory. In all, this Order changed the names of nearly 650 sites across the US, including 28 in Colorado. The BGN has been working to rename similar offensive sites like N—- Creek in Kansas and Savage Lake in Minnesota.

Why Mt. Blue Sky is Probably Sticking Around

Geographers aren’t the only American institution modernizing names. President Joe Biden authorized the Department of Defense to change the name of Fort Bragg to Fort Liberty in 2022. Braxton Bragg served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War, and US Army advisors found a military installation named after a traitor disrespectful. The Washington Redskins pro-football team also changed their name to the Commanders that same year. Even Frederick High went through a mascot change to adapt to modern sensibilities.

These changes have been dubbed part of the “woke agenda” by Trump and his allies, and Trump’s platform for president included changing back fort and monument names. However, legally changing geographic names is another matter. Official changes must go through the BGN and Congress.

Trump knows this: his executive orders charge the new Secretary of the Interior to initiate the renaming. Cabinet hearings are ongoing at the time of writing, but Trump’s nominee for the post Doug Burgum is expected to be confirmed. When Burgum and Trump’s other secretaries take office, they will appoint new members to the BGN. Burgum will ask the BGN to review Trump’s two renaming requests, and then the BGN will then hold public hearings. Unless the BGN objects to the name changes as a result of those hearings, the new names will be official.

This process of going through the BGN and holding hearings takes a while. For example, the hearings concerning Mt. Blue Sky started in 2019 and only finished in 2023. While a push from the president helps—Haaland got Order 4304 approved in under two years—geographic name changes take some time. While government offices will use Trump’s new names until the BGN decides, Trump wants his new names to stick. Thus, he will likely limit the number of name changes he’ll give the BGN and Congress.

It’s also worth considering why Trump is renaming Denali and the Gulf. Trump mentioned in his inauguration speech that he feels an affinity with William McKinley. Both ran businesses before they became the Republican candidate, both wanted to expand US borders, and both loved tariffs. While the mountain will be McKinley, the national park will remain Denali National Park and Preserve.

As for the Gulf, Trump has never had the best diplomatic relationship with Mexico. He accused Mexico of sending criminals over the border during his first campaign and proposed heavy tariffs against the country during his latest campaign. Rebranding to the Gulf of America is nothing but pure nationalist posturing. His Executive Order is titled “Restoring Names that Honor American Greatness,” and the order itself states its purpose as to “promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation.”

Mt. Blue Sky is no Denali. It’s not the tallest mountain in America or the largest body of water outside of an ocean to border the country. Given that the Trump administration has so much they are trying to accomplish in four years, its likely that Mt. Blue Sky isn’t worth the effort to rename. The political pushback to change a landform’s name in blue-voting Colorado would be significantly larger than in a red state like Alaska (where even Trump’s Denali rebrand is getting backlash). All things considered, recent Colorado renames are likely to remain.

Other Names Will Also Stick for Now

That said, the current Administration will likely resist any new name changes that don’t fall in line with their “American Greatness” ethos.

For example, advocates have been trying to remove Kit Carson’s name off one of Colorado’s fourteeners since 2008. Carson was a US general who starved and slaughtered thousands of Navajo during the 1860s. His cruelty to women and children and focus on concentrated kill zones have earned him comparisons to Adolf Hitler.

It’s doubtful that Trump’s BGN would remove the name of this renowned settler from the Colorado peak. They would likely also reject attempts to change the city, county, and military fort that bear Carson’s name. Other Colorado locals that have faced calls for renaming, like Redskin Mountain and the town of Chivington, will also likely remain for now.

But Will Trump’s New Names Stick?

The Trump administration must first jump two big hurdles to renaming Denali and the Gulf: public support and Congressional support.

According to its bylaws, the BGN must seek community consensus in changing a name. This means that if enough locals dislike a name, the BGN will support them. This makes sense: if locals hate a new name, they won’t use it, and if a name isn’t used, then it has no point. Given that local support drove the 2015 Denali name change, this alone may save the Denali name.

The BGN also considers if the geographic feature spans multiple countries, as can happen with a river, an ocean… or a gulf. While some Americans are all in on the Gulf of America, Mexico is understandably not having it. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum dismissively laughed at the gulf’s new moniker, saying that Trump coud call the gulf whatever he wants but “for us it is still the Gulf of Mexico, and for the entire world it is still the Gulf of Mexico.”

Indeed, the name change will only affect American maps unless other countries or the United Nations adopt the new name. There’s precedent for such a name divide: the river that defines most of the US-Mexico border. Americans call it the Rio Grande, and Mexico and the rest or the world call it the Rio Bravo.

Trump also has to consider that only Congress can solidify a geographic name change. Without Congressional approval, Mt. McKinley and the Gulf of America will only exist until another president cancels his executive order. While Republicans currently controls both houses of Congress, that could change after the 2026 election. Practically, the next two years hold Trump’s best chance to ensure his new names pass through the BGN and Congress.

However, congressional conservatives may not support the renaming efforts (and some already aren’t). Others may reject a name change based on cost. The government would need to pay to replace every sign, form, and official map (print and digital) with the old name. This is easy for unnamed features getting names or small regional features like a mountain or creek. However, new signage for over 1,700 miles of coastline and third-largest national park will be expensive.

If Trump does successfully get his new names approved by Congress, they are likely to stick for some time. Of course, if a name can be changed and changed back, then it can always be changed again. A future presidential administration could restore Denali’s name as well as other site names. They would also need public hearings and Congressional support, but it’s not impossible.

Unlike mountains, names aren’t set in stone.