The following review is for a film rated R by the MPA. The film contains graphic violence, violence against children and animals, excessive male and female nudity, and on-screen sexual acts.

Despite only having four films under his belt, Robert Eggers has forged a unique place among modern auteur directors by restricting himself to eerie period pieces based off centuries-old sources. His first film The Witch turned the diaries of Puritan colonists into a demonic nightmare. He then used eighteenth-century mariner logs to create his Lovecraftian tragedy The Lighthouse, and he next brought Shakespeare’s Hamlet back to its brutal original Danish roots in The Northman. Eggers’ latest project is both his most straightforward and mainstream adaptation as he takes on the oldest surviving on-screen vampire and SpongeBob Squarepants character Nosferatu.

For those of you not in the Frederick Film Society (which you all should be), here’s some film history: Nosferatu was originally a 1922 German silent film by F.W. Murnau. Murnau wanted to film Dracula, but Bram Stoker’s widow refused to give him the adaptation rights. So Murnau changed the names of the characters in Dracula and made Nosferatu. While the film was praised on release for its effects, makeup, and use of shadows, the Stoker estate demanded all copies of the film be burned. Partial reels survived until the 1970s when the sections of surviving film were reassembled. The 102-year-old film is now in the public domain—you can watch the whole thing on YouTube.

Since the movie is a knockoff of Dracula, the plot is basically the same as Dracula. Realtor Thomas Hutter (not Jonathan Harker) goes to Transylvania so he can sell a property in his hometown to a rich count named Orlock (not Dracula). After barely escaping from becoming Orlock’s snack and returning home, Hutter discovers that his wife Ellen (not Mina Harker) is next on Dracula’s meal plan.

So as not to get too close to copyright infringement, Murnau made large changes to the plot for his film. Instead of London, the film is set in Wisborg, Germany. The Count’s servant Renfield is changed from just a random guy to Hutter’s boss Knock. Whereas Dracula only attacks Mina after Jonathan tries to kill him, Orlock becomes obsessed with Ellen after he sees a picture of her in Hutter’s locket. Vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing, Mina’s best friend Lucy, and cowboy Quincey Morris (yes, Dracula has a cowboy in it) are cut completely.

The biggest change, however, is the ending. Dracula is finally stopped after he is decapitated and has a stake driven through his heart. In Nosferatu, Count Orlock is delayed from returning to his coffin full of graveyard dirt before dawn, so he turns to dust in the sunlight. The idea that vampires die if exposed to daylight isn’t found in Stoker’s novel but comes from Murnau’s film, as does the belief that vampires must sleep during the day and the image of vampires looking pale and corpselike. Nosferatu became as influential as Dracula on our modern conception of vampires.

Enough of the history lesson. Instead of a beat-by-beat remake like Herzog’s 1979 film, Eggers makes his film a blend of Murnau’s film and Dracula. Still set in Wisbourg, Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult) is asked by his boss Knock to secure an estate sale to a rich count by the name of Orlock. However, Count Orlock lives in Transylvania and is too ill to travel, so Thomas must go to Orlock’s castle. Thomas’ wife Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) begs him not to go because she’s worried his absence will cause her to go mad, so Thomas has Ellen stay with his friend Friedrich Harding (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and his wife Anna, a character not in Murnau’s original.

After a long journey by horse, Thomas reaches Transylvania but is warned by a band of Romani that he should avoid Count Orlock. However, the commission is too high for him to refuse, so Thomas meets with Orlock. Orlock is played masterfully by Pennywise actor Bill Skarsgård who completely disappears in the role. Granted, it’s easy to disappear when your character mainly exists as silhouettes and shadows, but the vocal performance is more deep and menacing than anything Skarsgård has done before.

Like in the original film, Thomas stays three nights with Orlock at his castle, seals the deal on Orlock’s new manor, and jumps out a window after Orlick tries to kill him. Meanwhile, Ellen is indeed going mad without her husband—her raving and convulsions are so bad that Harding ties her to the bed. Harding calls the local doctor Wilhelm Sievers (Ralph Ineson), who cannot cure Ellen with modern medicine but thinks his old college professor can.

They go to Professor Albin Eberhart von Franz (Willem Dafoe), which creates the biggest deviation Eggers makes from both his source materials. Von Franz is a clear analog to Van Helsing, and he almost immediately diagnoses Ellen as being possessed by evil. Ellen confides in Von Franz that she has always had the power to sense the supernatural and that, as a young girl, she called out for a guardian spirit to love her. Instead, she was beset upon by a beast and given epilepsy when she rejected him.

This beast was Orlock, who schemed with his now-insane servant Knock to bring Thomas to Transylvania, kill him, and let Orlock possess a now-grown Ellen.

In this way, Eggers makes his film a dark fantasy romance with gothic horror undertones instead of the scary gothic horror with possibly some romantic undertones that most vampire films follow. Most cinematic depictions of vampires, including Dracula, follow the template set by gothic literature where authors like Stoker used vampires to represent loose sexual morals and STIs. Even Murnau’s original film paints Orlock this way: his obsession with Ellen is sudden desire brought on by a photo in Thomas’ locket. Seduce, suck blood, and split is the way of the traditional vampire.

Egger’s film, however, depicts Count Orlock as more of a jealous ex-boyfriend to Ellen: he wants to get rid of her new man and wants her to be his one and only because of the supernatural connection they share. Ellen, meanwhile, knows that Orlock’s love (while tempting at times) is bad: she wants to be with and protect Thomas, whose love cured her of her childhood seizures. This love triangle is more akin to Twilight than Salem’s Lot as Eggers tamps down the blood and brutality and increases the quiet tension and lingering moments where the audience isn’t sure if Ellen will kiss Orlock or kill him.

Scratch that—Ellen’s plight is far more relatable than Bella’s. Instead of having two perfect hunks fighting over her, Ellen finds Orlock ugly and monstrous but cannot deny the connection they will always have that she can’t have with Thomas. While Thomas is nice and loving, he dismisses her concerns. There is also an entire part of herself that Ellen can’t and doesn’t want to explain to Thomas, and though Orlock is abusive and controlling, he does understand her. Given how others treat her because of her illness, it feels at times that Ellen even feels like she doesn’t deserve someone like Thomas and should instead be with Orlock.

Feeling ashamed of your past, thinking you don’t deserve love after an abusive relationship, dealing with a difficult ex… these relationships are not only more complex than those in typical vampire movies, but they are so relatable that they make 1838 feel contemporary and relevant.

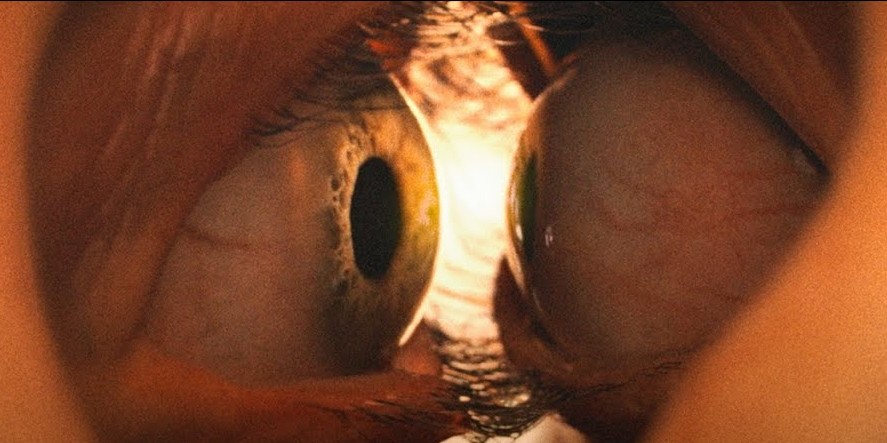

This tone and take on the vampire legend will undoubtedly put some audience members off from the movie, who are expecting something as gory and graphic as Eggers’ previous movies The Witch and The Northman. This isn’t to say there aren’t any scares: the scenes of Ellen wildly contorting from seizures are very unsettling, and the corpse makeup is nasty in its brilliance (especially the well-lit shots of Orlock). Still, don’t expect jump scares or edge-of-the-seat thrills.

The tradeoff for the lack of frights is spectacular character work and beautiful cinematography. Ellen is the role Lily-Rose Depp has needed—she’s been a great lead actress in not-very-great projects like Yoga Hosers and The Idol, but this film finally gives her material worthy her talents. Hoult does good work as Thomas and Dafoe is fun as Von Franz, though both characters are a bit shallow in their depth. Aaron Taylor-Johnson gives a surprisingly emotional performance as Harding, and Ralph Ineson from Eggers’ The Witch grounds the rest of the characters with his measured but compassionate portrayal as Dr. Sievers (plus, he’s a dead ringer for Murnau’s Sievers).

Eggers’ visuals are, as always, stunning. While his use of shadow isn’t as revolutionary as it was in Murnau’s time, it’s incredibly compelling to show just a little of Orlock at a time. More than darkness, Eggers uses light to amplify the horrors of the film. While unlit hallways and dank cellars are used liberally for threats the audience isn’t sure are there, the ravages of plague and rat-eaten corpses sit in full daylight where the viewer can’t escape them. Firelight is also used this way: there’s a scene where Orlock is stalking his prey that could be all in shadow, but Eggers has torchlight illuminate Orlock’s movements as he gets closer, making his approach even more intense.

Nosferatu may not live up to its marketing as a horror film, but it is a great piece of cinematic art that does something different with old-fashioned tropes. While teen audiences may find the film a little slow or melodramatic at times, this dark fairy tale will keep those that are mature enough for its content on edge until its jaw-dropping final scene. While I’m not wild about the plot point where dismissing medical science saves the day, its inversion of the typical vampiric tropes is reason enough to give it a watch. The grand visuals need to be seen on the big screen, so go with friends—it is a Christmas movie after all, not just in its release date but in its setting.

Nolan Przybyciel • Dec 27, 2024 at 10:17 am

Honestly thought that was the scariest vampire movie ever made, or atleast the scariest vampire. I mean cmon there is literally no version of dracula even remotely as scary as that nosferatu. Copollas was a Gothic romance, that was sheer darkness and terror