Junior Zach Burton has played basketball for 10 years, and now that he is on Frederick High’s Varsity boys basketball team, he’s in it to win it. Zach is a junior transfer student who came to Frederick with a goal: win state. “Winning state would mean it was all worth it since I am a transfer student,” said Zach. “It would be disappointing if I didn’t win because I came here to win.”

Students like Zach are driven by achievement pressure Achievement pressure is the expectation that students always give the maximum effort so they can earn the highest grades, fastest times, lead role, most points, or the first chair. High school is full of prizes to win, from homecoming crowns to academic honor roll to NAHS graduation cords, and the students that feel a lot of achievement pressure try to win as many as they can.

High school is and has always been a place where achievement is at the forefront. School constantly measures which students are achieving (and which are not) through class grades, class rank, GPA, scoreboards, team rosters, and the dozens of student awards and accolades given throughout the year. The commons is dominated by a trophy case full of past victories by athletics and music, and the walls of the lower D and E wings are adorned with framed works of award-winning student art. Students are even encouraged to wear a public scorecard of how much they’ve achieved in the form of a letterman jacket adorned with letters and pins.

Not even all of us at the Frederick Lantern are immune from the drive to achieve more. The bottom of our homepage lists our Distinguished Site Awards, and we constantly look at site analytics to see which stories are popular, how many readers are coming to our site, and how long we are engaging our readers. When we reach our goals, we immediately go after new ones: for example, after celebrating that we finally gained over 500 Instagram followers, we set a new goal of getting 575 followers (one more than Mead High’s student news site).

But this push to be the best and do more doesn’t just win students followers, congratulations, and awards—it also burns them out.

A study by Common Sense Media found that 53% of teens surveyed said that the pressure to achieve negatively effects them on a regular basis, with 1 in 5 saying that the pressure is so intense that they are starting to burn out on school. While there are six different pressures that lead to teen burnout, achievement pressure is the second-most common. Teen girls are 32% more likely to be negatively impacted by achievement pressure than teen boys, and nonbinary teens are twice as likely to burn out from this pressure than their cisgender peers.

What makes achievement pressure different from other pressures on students is that achievement is seen by many students as a “good thing,” even those who feel it is burning them out. One reason for this is because achievement pressure is closely tied to “game plan” pressure, or the pressure for students to have their future after high school all figured out before graduation.

Students that are college bound are entering a highly competitive environment to get into a major program, so they must have stellar grades and a long list of achievements to stand out from the crowd. This can also drive achievement pressure in sports, as many students doubt they can afford college without an athletic scholarship to help get them there.

Students going straight into the job market need to have experience, training, or expert skills so they can compete with older candidates in a narrowing job market. Even students bound for the military have to pass the ASVAB exam, and those wanting to join the officer’s corps or attend a military college need a resume as packed with achievements as any student trying to get accepted into their college program.

Since achievement pressure is so closely related to game plan pressure, it makes sense since the Common Sense Media survey found that the top source of game plan pressure is also one of the top sources of achievement pressure: school adults like teachers and counselors. Out of all the teens that reported that they felt achievement pressure regularly, 38% said that school adults were a major contributor to this pressure.

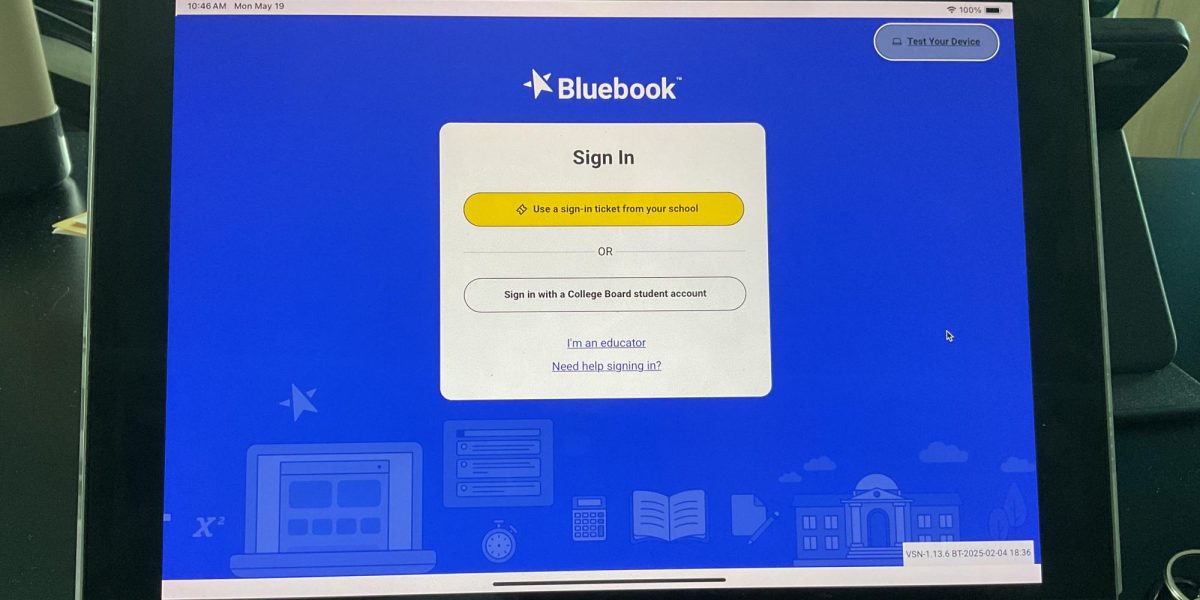

Teachers cause achievement pressure by measuring how well a student performs in the teacher’s class based on test scores, practice assignments, and projects. Counselors do the same thing but for every class, and they pressure students to do well on the PSAT and SAT tests. Coaches also set high expectations for their players to work hard and win, creating achievement pressure for student athletes that can be overwhelming.

The thing is, it’s hard to blame teachers, counselors, and coaches for being focused on student results because that’s their job. It doesn’t make sense for someone to get mad at their personal trainer for increasing the weight they lift or say “they just don’t like me” about a doctor that shows the results of a blood test indicate a health issue. But kids do this all the time with teachers because the pressure to do well comes from everywhere. You don’t see a dozen doctors every day that tell you that you have to get healthier, but students will hear the message of “do more and do better” from every adult at school every time they see them. It’s their job, sure, but it’s overwhelming.

Another group of adults contributes to this pressure, as 1 out of 3 students surveyed said their parents were a major source of the pressure to achieve. Many parents want their children to succeed and they push their children toward activities and behaviors they deem will help make them successful in life. This sometimes leads to conflict when a parent wants a teen to achieve something that they don’t want to or can’t realistically achieve.

While teens try to appease school adults mainly to get them off their backs, the students that feel pressured to achieve want to make their parents proud of them. This is a key reason why LGBTQ+ teens feel more pressure to achieve than their cisgendered classmates—over half of all LGBTQ+ teens who have come out experience some degree of rejection for their gender orientation from at least one parent, so they feel more pressured to use other measures like grades and awards to make their parents proud of them again.

However, the top source of achievement stress is the student themselves. Nearly half (48%) of students say that the pressure to achieve more comes from within, but the reasons for this are varied. Some students reported that they try to achieve as much as possible out of a sense of insecurity, and others said they motivate themselves to achieve because they have big dreams that require a lot of work. Most respondents, however, said that their drive to achieve comes from their desire for respect and status.

Social media is a big contributor to this desire for respect and status because social media has made comparisons to others easier than ever. Awards, sports victories, and standing ovations for a concert performance are all moments that can be shot and shared. While teachers cannot post grades publicly, students have a pretty good sense of who is at the top of the class and who is at the bottom based on how students act in class and the students own status updates about their grades.

This is why social media is a mixed bag when it comes to achievement pressure: 7 out of 10 students say that social media sometimes makes the pressure to achieve worse because they feel that others are outclassing them, but 5 out of 10 students say that social media sometimes makes the pressure to achieve better because they see that they are in a better position than others.

It’s important for teens to figure out how to releive their achievement pressure because it is a source of stress that lasts beyond school. Almost every workplace has pressure to achieve more, with managers evaluating employees based on how much they are able to get done, how many sales they make, or how celebrated their work is by customers or the industry.

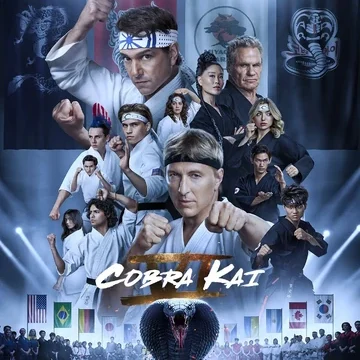

The best way for teens to mitigate achievement pressure is to spend time with their friends. Friends tend to be supportive and not competitive, even when playing games and on a different team. In fact, playing games is a great way of relieving achievement pressure because it help you practice how to lose and learn that setbacks and not winning everything isn’t the end of the world. This is why 50% of teens use video games (both console games and mobile games) to relieve the stress caused by wanting to win, and it works because 1) wins come pretty easy, and 2) loses don’t really matter because you get to play the level over again.

By contrast, having a lack of friends increases achievement pressure. This is why good coaches take time to build cameraderie between team members and expect players to have one another’s backs: a team that doesn’t support one another starts trying to compete against their other team members instead of the other team.

“As a former athlete, [sports] put a lot of pressure on me because I felt like I didn’t have anyone [on the team] there for me, and it really affected my relationships with my other friends,” said freshman Jose Cortez. “I felt pressured to do my best and keep this smile on my face when I was struggling the most.”

Some teens that struggle with the pressure to achieve too much need to set more realistic goals and ble to say no to too many comittments. While it’s important for students to always do their best, people can’t always give 100%. They get tired and need breaks, and they can only fit so many activities into their day.

Finally, it’s important to be happy with smaller victories in life and find happiness in achieving something if not everything. Not just students but adults should not dwell on perfection to the point where they cannot see all the good that happens, though that’s hard for students like Zach Burton, who feel that it’s either win it all or lose everything.

“I wouldn’t be happy if I didn’t win,” he said, “because I feel like I have this year to win it all.”