This is the second article in a series examining teen stress and burnout. You can find the first entry in this series here.

Freshman Sabrina Guardado knows what stress is like.

“First is English because there are too many assignments and I can’t get help or an extention. There’s Biology–I got a 95 out of 100, but I still have a C and I don’t know why. I didn’t do well on my last algebra, and I can’t retake it, so I don’t know what to do. I don’t want to fail any of my classes, but it’s hard to stay on top of everything.”

She’s not alone: a recent study by Common Sense Media showed that more than 1 in 4 high school students are so stressed that they are burning out. Students are succumbing to feelings of burnout due to six key factors: the pressure to have a “game plan” for their future, the pressure to achieve as much as they can, the pressure to look good, the pressure to participate in an active social life, the pressure to unconditionally support friends, and the pressure to do good in the world through activism.

While the study is clear on the psychological effects of these pressures, it doesn’t really explain what these pressures do. They cause stress, sure, but what exactly is stress?

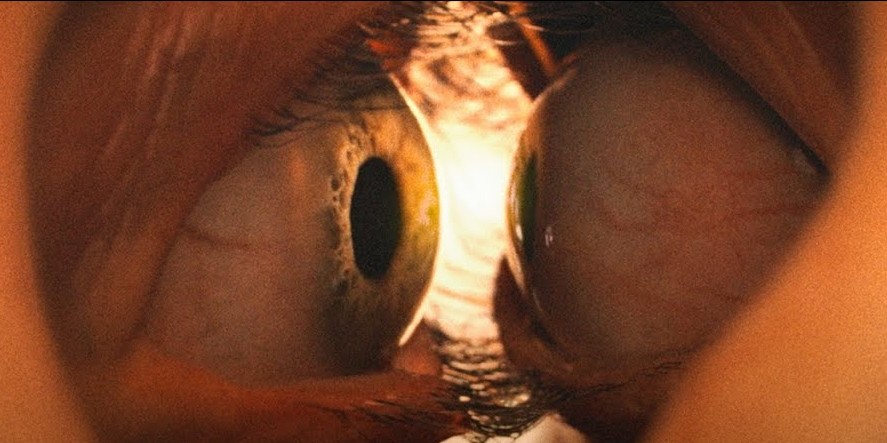

Stress occurs when an outside stimulus (called—what else?—a stressor) that threatens or challenges the body. A hungry tiger could be a stressor, but so could being in the cold without a coat. Stressors aren’t even always bad things—seeing your crush or trying to score a goal for your team are stressors too. Stressors trigger the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a system between the brain and hormone-producing glands that decides which hormones to release to help us respond to the stressor:

- If the stressor is a threat to the body’s safety (like the tiger), the adrenal gland is triggered, which produces adrenaline and fuels a flight-or-fight response.

- If the stressor is something the body must endure (like the cold weather), the adrenal glands release norepinephrine, which increase awareness muscle activity (like shivering or shaking)

- If the stressor is something the person desires in spite of the stress it may cause (like the crush or scoring the goal), the adrenal glands produce androgens like testosterone in men and estrogen in women, which heightens attraction to the opposite sex and a sense of competition with those of the same sex.

- No matter what the stressor is, the adrenal glands produce a lot of cortisol.

Cortisol is a hormone that tells the organs of the body what to do and, when paired with another adrenal hormone called aldosterone, is responsible for homeostasis, or the steady regulation of the body. Aldosterone controls blood pressure and kidney function, and it tells the brain when you are thirsty. Cortisol makes sure the body has enough energy by regulating blood sugar and the metabolism of food into proteins, fats, and carbohydrates the body can use—cortisol is what tells the brain that you are hungry. Cortisol also tells the body when to conserve energy and is responsible for your sleep cycle.

A stressed body needs more energy—to outrun the tiger, to keep warm in the cold, to kiss the crush, to score the goal—so every stressor results in more cortisol being pumped into the bloodstream. Blood sugar goes up, awareness goes up, and blood pressure rises. Another affect is that the excess cortisol tells the rest of the endocrine system to shut off the immune system, as the body’s immune response is built to slow the body down so it can heal, which explains why some injuries only result in pain and swelling once a fight is over.

The human body needs cortisol, and the occasional spike in cortisol isn’t harmful. Excessive stress, however, and as a result, a high amount of cortisol is very bad for the teen body in several ways:

Stressors and the side effects of excessive stress commonly result in anxiety. When asked, most students say that anxiety and stress are the same thing. It’s easy to confuse the two: anxiety and stress have similar causes and similar physical responses. However, anxiety is an emotion based around fear of an unknown future, while stress is a physical condition. While both are “feelings” of pressure, anxiety lives in the mind and stress lives in the body.

How does someone know if they are suffering from stress or anxiety or both? First, consider what is causing the sense of pressure—if a stressor cannot be identified, it’s anxiety. If a stressor does show up, see if the pressure goes away once the stressor goes away—if it does, that’s stress; if it doesn’t, that’s anxiety. Anxiety typically lingers after the source of stress is gone, and if one suffers from an anxiety disorder, it never really disappears. Stress can’t do this because it needs an environmental trigger (though anxiety can become a stressor for a person).

A more basic difference between stress and anxiety is how the person feels when put under pressure. If the person feels overwhelmed, that’s stress; if they feel worried or afraid, that’s anxiety; if they feel overwhelmed and worried, that’s both. There is also one physical reaction that differentiates stress and anxiety: sweat. Cortisol burns energy, which creates heat, which makes a person sweat—if you aren’t sweating, you aren’t stressing.

The best way to reduce stress is to remove the stressor, but there are some stressors like the pressure to look good, the pressure to be a supportive friend, or the pressure to achieve high grades that are inescapable—at least until graduation. Luckily, there are other ways to deal with the body’s stress reaction:

- Trigger your endorphins: Cortisol exists at one end of the HPA axis. At the other end are the pituitary gland and hypothalamus, which create hormones called endorphins. Think of endorphins as the anti-cortisol: they activate the immune system, relieve pain, relax muscles, elevate mood, lower blood pressure, and regulate appetite. Easy ways to trigger endorphins include exercise, massage, deep breathing, laughing, acupuncture, eating a favorite food, bathing, and going on a romantic date.

- Set a bedtime and don’t hit snooze: Teenagers need a lot of sleep (8 to 10 hours, according to experts) but they also need regular sleep. Set up a schedule where you go to sleep at about the same time every night (ideally before 11 p.m.) and wake up at the same time every day. This creates a circadian rhythm for the adrenal glands, and once they get into a routine, it becomes harder for overproduction of cortisol to break that routine.

- Cut caffeine and sugar: Cortisol is already pumping up your blood pressure and burning energy. Other substances that increase energy production in the body, like sugar and caffeine, only make the problem worse. Caffeine is also a diuretic that pushes water out of the body and into the bladder, and this can compound the diuretic effect of cortisol and leave the body dehydrated.

- Water, chamomile, and strawberry-banana smoothies: Instead of sugar and caffeine, hydrate with water to combat the effects of cortisol. Another drink that can lower cortisol is chamomile tea (which isn’t real tea because it doesn’t have caffeine). Foods rich in magnesium can also combat cortisol, as magnesium relaxes the body and “resets” the adrenal glands if one of its hormones is out of whack. Foods that contain high levels of magnesium are peanuts, black beans, spinach, avocados, blackberries, potato skin, dark chocolate, pineapples, bananas, and strawberries.