“Cracking open a cold one with the boys” is a well-known meme, but everyone our age knows that it’s used ironically. For the entirety of Gen Z’s existence, the legal drinking age has been 21. But as you chat with your grandparents and uncles this Thanksgiving, you may be surprised to hear that cracking open a cold one with the boys was pretty common in high school when they were teens. In some countries, like Mexico and France, the legal drinking age is still 18 years old, but Colorado decided this was too young not too long ago.

So when did the drinking age in Colorado become 21? And why?

Most of the first Americans to settle in Colorado were miners hoping to get rich during the 1858 Colorado Gold Rush. Mining camp towns were quickly established, and the first permanent building in most towns was the saloon, which was a place where the miners could not just get something to drink but a hot meal, mining supplies, groceries, a game of cards, and even someone to spend the night with. Nearly every man drank liquor because it was more reliably free of germs than most water sources.

As Colorado grew, saloons evolved from informal community meeting places to the centers of local government and mining unions. In 1861, the Rocky Mountain settlements officially became the Colorado Territory, and government functions started moving out of the bars and into the town halls. There was a movement in the 1870s to “civilize” Colorado territory so it could become a state, and new settlements like Union Colony (later Greeley) and Chicago-Colorado Colony (later Longmont) forbade alcohol to differentiate their communities with the rough mountain mining towns.

By the turn of the century, there were several temperance groups in Colorado (and every other state) like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and Anti-Saloon League that wanted to ban all alcohol statewide. These groups teamed up with the Ku Klux Klan, who was the largest political organization in the state at the time, to create a campaign connecting alochol to crime, immigrants, and Catholics. The teatotalers succeeded on November 3, 1915, when Measure 2 passed with 52% of the vote.

Starting on New Year’s Day 1916, Colorado was a dry state where “intoxicating liquor” sales and consumption were illegal–this included everything that was more than 0.5 percent alcohol. The rest of the country joined Colorado in 1919 with the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment. The laws were enforced by “purity squads” (who were mostly KKK members) who infringed on the civil liberties of anyone suspected of drinking.

This led to an extensive underground alcohol market and the introduction of organized crime in the state. To avoid suspicion, most of the illegal alcohol production and distribution in the state was done by women. Once police discovered that women were doing this, they added women to the police force for the first time. The alcohol ban encouraged gender equality on both sides of the law.

In 1932, 67% of Colorado voted to repeal prohibition. While this was initially just a protest vote because alcohol was illegal nationally, Congress changed the definition of “intoxicating liquor” from 0.5% alcohol content to 3.2% soon after Colorado’s vote. Since men could traditionally drink at the saloon as soon as they could work in a mine regardless of age, the Colorado legislature set the age to buy 3.2 beer at 18.

Colorado celebrated the change in liquor laws with “New Beers Day” on April 7, 1933. Later that year, 1933, Colorado and thirty-five other states ratified the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed the Eighteenth Amendment and legalized all alcohol. While some states like Utah kept statewide prohibition, most states took the recommendation from the government to set the minimum age for buying alcohol as 21, which at the time was the same minimum age to vote.

Colorado split the difference. A Coloradan needed to be 21 to buy “malt, vinous, or spirituous liquors” like wine and whiskey, but they could still buy 3.2 beer at 18.

In the 1960s, alcoholism was declared to be a mental illness by the medical community, and President Richard Nixon allowed the National Institute of Health to start studying alcohol abuse in 1970. A year later, the Twenty-sixth Amendment was passed and lowered the voting age to 18 from 21. Several states that made the drinking age 21 to match the voting age after Prohibition consequently lowered the drinking age to 18 that same year to match the new voting age.

Colorado didn’t change anything: 18 for 3.2 beer, 21 for all other liquors.

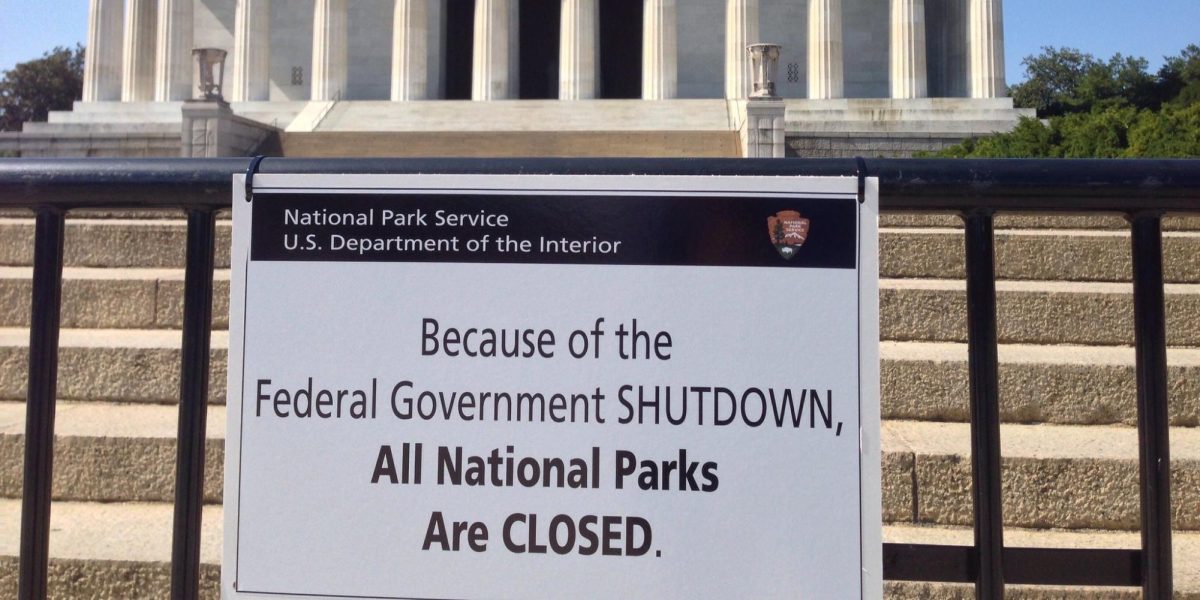

The result of the lowered drinking age was a sharp increase in car crashes across the states that lowered the drinking age, and the increase almost exclusively involved drunk driving by those under 21. Congress wanted to combat this by raising the Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA) to 21 across all states, but the Twenty-first Amendment banned the federal government from creating any restriction on state alcohol laws. So in 1984, Congress got around this by passing the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, which asked states to voluntarily raise their MLDA to 21 by October 1987 or else see a 10% reduction in the federal funds they get to maintain highways.

Colorado raised the state’s MLDA to 21 in spring 1987, though anyone who was already 18-21 at the time was still allowed to buy 3.2 beer. Every other state as well as Washington, D.C., American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands set a MLDA of 21 too, though the MLDA remains 18 in US territories Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands (Guam set a MLDA of 21 in 2010). This effort paid off, as alcohol-related deaths dropped and teens drink less now than ever before.

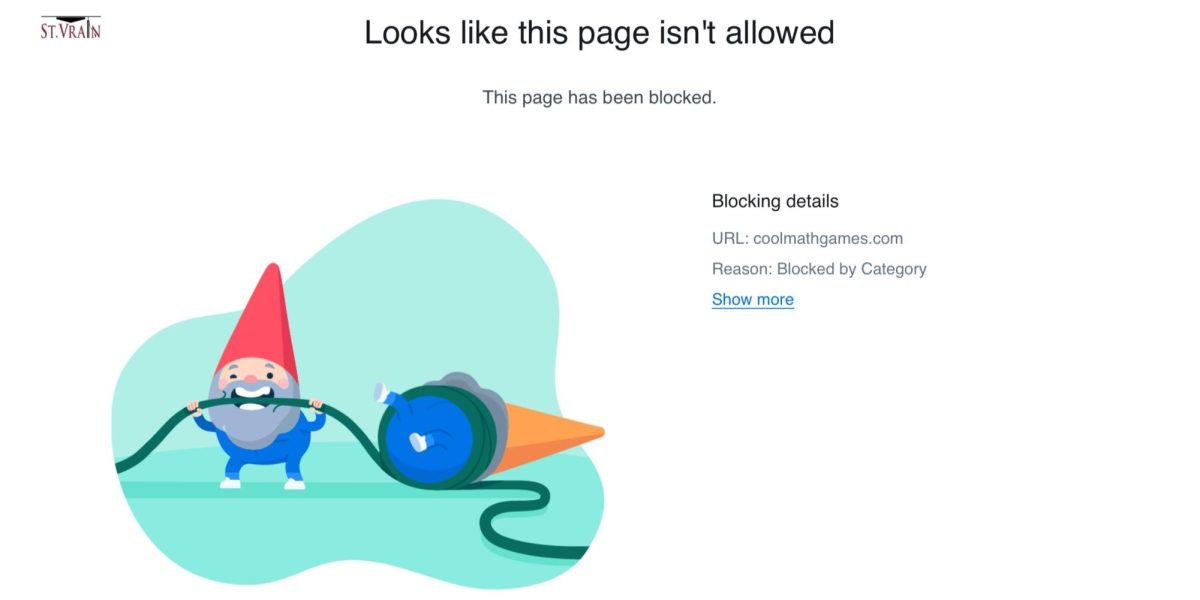

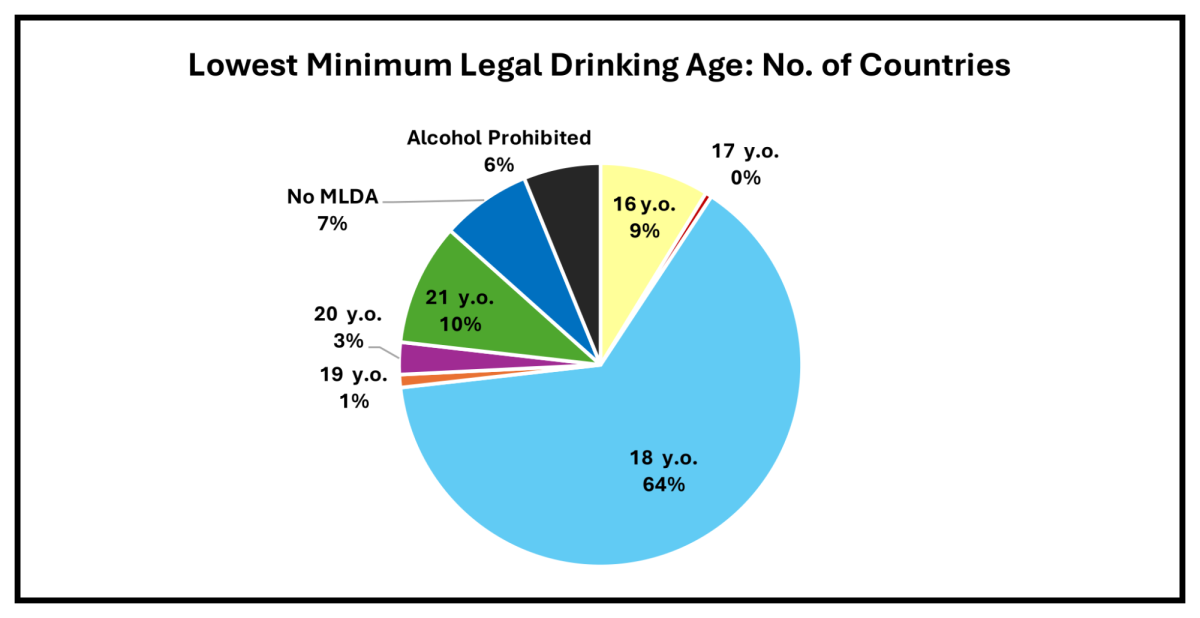

There are still debates on whether the drinking age should be returned to 18. In 2018, an initiative to lower the MLDA in Colorado to 18 failed to make it on the ballot. The initiative’s arguments boiled down to realigning the voting age and MLDA (they can go to war but can’t buy a beer), the reality that only 10% of the world has a MLDA of 21 while 77% have an MLDA under 21, and that teens find ways to get alcohol anyway. The last point seems to have some support from data: a survey by the Partnership for a Drug-Free America found 73% of teens have a friend who drinks alcohol at least once a week (though only 1 in 7 teens admit to drinking once a week), and that nearly half of teens see no risk in having five drinks.

Freshman Jose Cortez is one of these teens who thinks the MLDA should be 18 again. “Changing the drinking age will benefit 18-year-olds because it would teach them to be independent in a way, and they would also be looked upon as an adult.”

Freshman Melinda Yim agrees. “18-year-olds should be looked at as adults since they are starting or continuing working and going to college and have more responsibilities,” Yim said. “With that, they should have the same laws applied to them as adults by allowing them to drink at 18.”

While these are reasonable arguments, they don’t address the key reason the MLDA was changed to 21 in the first place: public safety. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention recorded a 16% drop in road fatalities in the states with an MLDA of 18 when they raised the MLDA to 21. This is a key reason for why the US has a higher MLDA than other countries: European countries like England and France are smaller and most people take public transportation, but the size of America results in most people driving themselves. Organizations like Mothers Against Drunk Driving that fight to keep the MLDA at 21 crop up in America and not Europe because driving–drunk or otherwise–is much more common in America.

Lowering the drinking age will also be inviting other dangers to teenagers. Teen bodies are still developing, especially the brain, and underage drinking can slow brain development, delay the end of puberty, and increase a teen’s propensity for violence. Alcohol also increases depression, which teens are already struggling against in record numbers. Lowering the drinking age to 18 would also allow some high school students into bars with adults and put them at risk of assault by others older and stronger than them.

“Since 18 year olds are still teenagers and their minds are still developing, they are most likely to be irresponsible and cause danger to themselves and people around them,” junior Maddie Roybal said.

Studies also show that alcohol is more addicting the earlier someone starts drinking, so lowering the drinking age would lead to more alcoholism. This alcoholism would also spread across all ages because, just as colleges struggle with 21-year-old senior students buying alcohol for their underclassmen friends, high school seniors would be able to buy alcohol for their younger friends (this is called a straw purchase). Eleven percent of teens already abuse alcohol, and this number would surely go up if teens could make straw purchases for other teens.

“21 year olds are more responsible than 18 year olds, who are still teens,” freshman Lizbeth Hernandez said when discussing why the MLDA should remain 21.

Although teen opinions on changing the drinking age are split, keeping the MLDA at 21 inarguably saves thousands of lives every year. Drinking at 18 is dangerous because they are not responsible yet; when you’re 21, you have more sense of responsibility and understand the problems of alcohol abuse more than teenagers who are drinking. Like with other popular legal addictive substances like tobacco and marijuana, waiting to try alcohol may be hard for teens, but the wait is worth it to ensure that they can handle those dangerous substances responsibily.