Usually, when someone thinks of accidents and deaths in the construction field, their mind goes to stuff like falling, crashed equipment, or electrocutions. Recent studies, however, have found that there is a more prominent risk of death in the construction field: suicide.

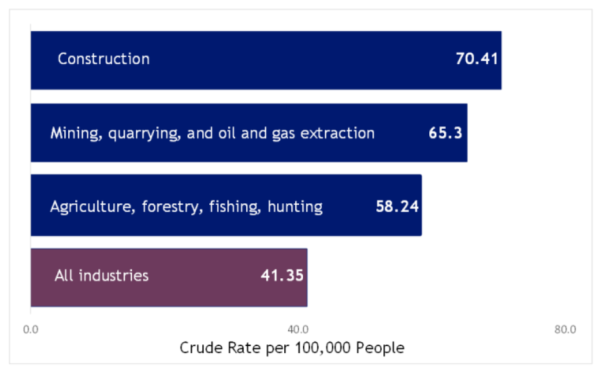

This is especially true in Colorado: according to the latest legislative report by Colorado’s Office of Suicide Prevention (OSP), which was published in November 2023, 13% of the Colorado adults who died by suicide in 2021 worked in construction, making it the deadliest profession when it comes to taking one’s own life. The report goes on to state that around 70 construction workers out of 100,000 will die by suicide in Colorado—this is much higher than the 41 per 100,000 average of all industries combined.

This grim statistic has a significant impact on Frederick and the surrounding community. Construction is the third biggest industry in Weld County, making up around 13% of the local workforce. Not only are a good number of the parents, uncles, and aunts of Frederick High students working construction, but Frederick High School students themselves work part-time construction over the summer and occasionally during the school year.

With this report, Colorado has identified construction work as an “industry at at higher risk for suicide,” which includes emergency responders, those involved in oil and gas drilling, miners, and workers involved in agriculture and forestry. What makes the numbers about the construction industry so troubling is the number of people employed: according to the Federal Reserve, around 176,500 Coloradans are working in construction compared to 22,300 working in mining and logging, 153,700 working as emergency responders, and 9,300 working in “utilities” (the umbrella term for oil, natural gas, wind, and solar energy extraction workers).

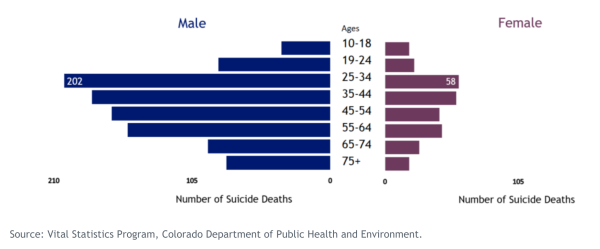

The CDC has conducted several studies in recent years to try to discover the main cause of the alarming suicide rates in construction. One contributing factor is that the construction industry is 93% male, and male adults commit suicide at a higher rate than females at every age, with the OSP seeing a spike in males 25–54, who commit suicide at nearly four times the rate as females of the same age.

Work-related stress can also have severe impacts on mental health, and construction is a particularly stressful job. The National Institutes of Health list the causes of these stresses as “inappropriate safety equipment, lax safety culture, high workload and long working hours, physical pain, [and] low social support from direct supervisors or co-workers.” Research by the Construction Industry Rehabilitation Plan, a mental health and substance abuse treatment program for Canadian construction unions, claims that 83% of North American construction workers have “experienced some form of moderate-to-severe mental health issue.”

An additional stress for construction workers in Colorado is that much of construction is seasonal work. For example, pouring concrete can’t happen during most of the winter, so many masonry workers who pour concrete in the summer are left unemployed in the winter.

Another big problem is injury. There’s no way to get around them in construction: workers use their bodies to lift heavy objects, work with dangerous tools, and stand in precarious areas of unfinished buildings. Accidents happen: the US Bureau of Labor Statistics claims that, over the course of a year, 4 out of every 100 Colorado construction workers will suffer an injury that will prevent them from working, either temporarily or permanently.

BLS notes that these statistics are probably lower than reality, as they come from workman’s compensation claims filed by construction workers; this means the statistics are not counting injuries to independent contractors (since they have no workman’s comp guarantees) or many of the 30,000 undocumented immigrants that work in Colorado’s construction fields—though these workers are entitled to workman’s comp under state law, few claims are reported, as reporting injury may result in deportation.

The problem isn’t just the injuries; it’s how they are treated. Many work-related injuries lead to the worker having to take opioids and painkillers. This can lead to addiction and dependency: according to research by the American Addiction Centers, 15% of US construction workers have a problem with substance abuse, while only 8.6% of the general population have the same issues. Construction workers are twice as likely as the average American to suffer from alcoholism, and more than 1 in 10 construction workers reported using illegal drugs.

All these factors together explain why suicide has spiked in the construction industry. This suicide rate is particularly bad in Colorado because all suicide rates are pretty bad in Colorado: Colorado ranks sixth as the state with the highest suicide rate, and suicide is the eighth most common way to die in Colorado, outranking both liver disease and diabetes.

The good news is that Colorado is working to reduce suicide rates in the state. One of the primary resources Colorado uses with men in the construction industry considering suicide is Man Therapy, a website that uses humor and psychology to help men who wouldn’t otherwise go to therapy process their negative feelings. Several construction sites in the state have been trained in Man Therapy’s de-escalation techniques to help talk down a suicidal person.

The good news is that Colorado is working to reduce suicide rates in the state. One of the primary resources Colorado uses with men in the construction industry considering suicide is Man Therapy, a website that uses humor and psychology to help men who wouldn’t otherwise go to therapy process their negative feelings. Several construction sites in the state have been trained in Man Therapy’s de-escalation techniques to help talk down a suicidal person.

Colorado’s OSP has also implemented the Sources of Strength program to improve mental health in 11 school districts (including St. Vrain Valley), brought the Gun Shop Project to all Colorado counties, and funded the creation of the Spanish version of Man Therapy. One of their most successful programs to date is the Follow Up Project, which checks in with those who have attempted but survived suicide weeks and months after the attempt to make sure that the individual is on a better path.

If you are going through a major personal crisis and need to talk to someone about it, you can contact the Teen Crisis Center at (800) TLC-TEEN or the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 988. Asking for help is always a strength, never a weakness.