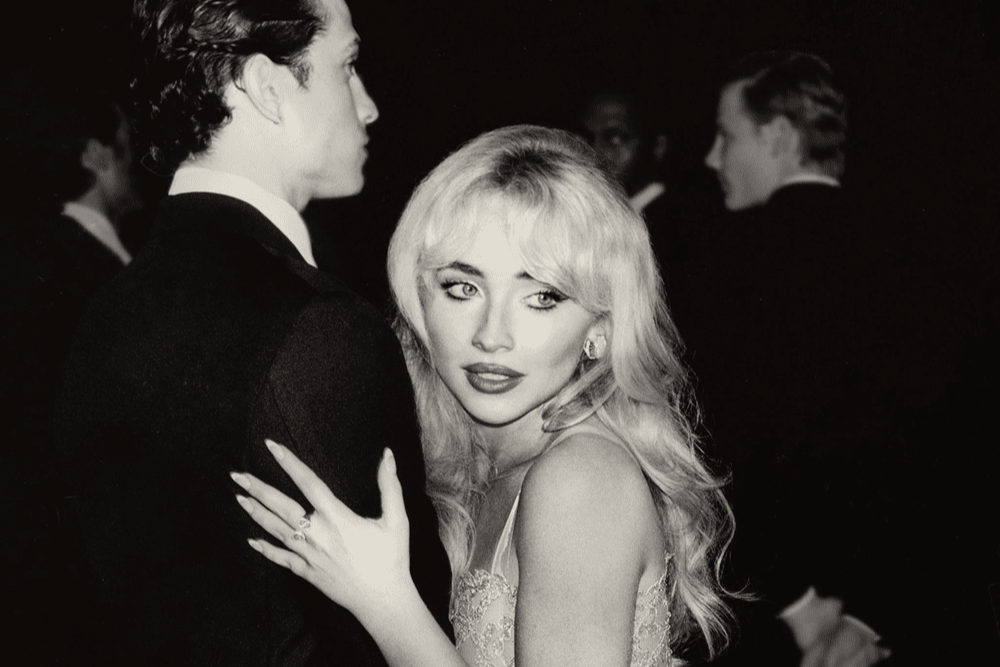

One of the most harrowing actions that drama students must perform onstage has nothing to do with heights, fights, or other physical risks—it’s the stage kiss. From Beauty kissing her Beast to the Music Man kissing his librarian, this kind of public PDA is required in most dramatic productions. Yet kissing is typically a very intimate act between two people, and these students are expected to lock lips with someone they did not choose as a partner in front of hundreds of people. How do they do it?

The answer is through intimacy coordination. Intimacy coordination is the process of staging any gentle onstage physical contact, similar to how theatres have had fight coordinators for decades to stage rough physical contact… and both are done for the same reason: actor safety. Through intimacy coordination, student performers are able to perform embraces, caresses, and even kisses demanded by the script in a way that protects them emotionally.

The most surprising thing about this process isn’t that it’s happening; it’s that it is student-led.

Kissing Coach: The Job of the Intimacy Coordinator

This semester, junior Peyton Siders served as the Intimacy Coordinator (IC) for Almost Maine, High Fidelity, and The Madwoman of Chaillot. As Theatre Vice President, Peyton had the leadership skills and close relationships with her fellow actors that made her an ideal candidate for IC.

Peyton discussed what she does as an IC: “I schedule rehearsals, and I teach [actors] about consent and comfortability. After I make sure everyone feels good, I bring in each couple individually and slowly work up to whatever intimacy Mr. Coon [the director] pictures for the scene.”

According to Peyton, it is important that the IC is a go-between for the adult director and the student cast members so students never feel pressured by an adult to do something they find uncomfortable. Instead, Peyton outlined how Mr. Coon taught her how to choreograph intimacy and how they came up with a plan together of what the scene should look like before Peyton worked with each couple. “A hug above the shoulders means something entirely different than a hug at the waist,” Mr. Coon said. “The first is friendly and platonic, while the second is implicitly romantic.

As soon as actors are cast in their roles, the director gives the IC a list of who engages in intimacy, and the IC schedules a private intimacy rehearsal to ease the nerves of performers. “It’s just me and the couple,” Peyton said. “[The director] Mr. Coon is around if we need him, but he’s not in the room because things are awkward enough without a teacher watching the whole time.”

Being the IC can feel really awkward in itself at some points. “It may be awkward, but I do this so I know my friends are supported and so they have someone they at least feel relatively comfortable with.” To help alleviate her awkwardness, Peyton said that Mr. Coon gave her extensive training on how to make actors feel comfortable and how to work through issues that can arise.

“Intimacy coordination is a tough but important job,” Mr. Coon added. “At the end of the day, teenagers are still developing emotional maturity, and for some their first kiss may be at a rehearsal or on stage. There are intense emotions at play. That’s why I have an older student as my IC, as it’s easier to talk through hormones and angst with a peer rather than an adult.”

How to Kiss: The Process of Staged Intimacy

This semester, Peyton worked with eleven different student couples: six for Almost, Maine; three for High Fidelity; and two for The Madwoman of Chaillot. Scheduling these rehearsals wasn’t always easy due to how intimacy works. “We had to move dates around because some people weren’t in the right headspace that day,” Peyton said. “Like when someone was going through a breakup at the time—it wasn’t the best time to be doing [intimacy work].”

These are the ground rules that apply to initial intimacy work that Peyton establishes at the start to keep everyone comfortable when working through intimacy. (Courtesy of Brandon Coon)

When the actors are ready to choreograph the intimacy, Peyton explains how consent works. “I first make sure the actors know that no one can make you do anything in the space and that you can say, ‘No, I’m not comfortable with that,’ at any time. If someone felt uncomfortable, it was my job to be there to advocate for them to the director and figure out a way to stage the scene differently.”

Once the actors know about consent, they each express where on their body is okay to touch and where is not okay to touch. “Everyone is different, and no assumptions can be made,” Mr. Coon said. “We had one actor who was fine with kissing and close contact but couldn’t have anyone touch her neck.”

Actors then establish a button, which is a word that anyone can say to take back their consent if the work gets overwhelming. Actors can withdraw their consent at any time, even on the day of the performance. “Normally this doesn’t happen,” Peyton said. “This is why I start early with intimacy. By the time the play comes, actors are comfortable enough to go through with it no matter what.”

Then comes time to act. Peyton first asks actors to shake hands, then hold hands, and keeps working up from small intimate acts like these up to what is needed for the scene, including long-held kisses. “For Madwoman, we need one couple to hold a kiss for about 25 seconds,” Mr. Coon said. “What’s funny is that the two were dating in real life but still needed the intimacy work because they rarely kissed in public, and this would be in front of all their friends and family.” Not all intimacy work is that developed: the intimacy one couple working with Peyton had to do was holding hands, while another couple needed to stage mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

A Culture of Consent

Ultimately, intimacy coordination is about consent. Whether onstage or offstage, students need to know that they are in charge of their own bodies and that no one may touch them in any way without permission. “It may seem silly to teach someone how consent works when they are just hugging or holding hands, but it isn’t. You can’t create a culture of consent if certain contact is worth choreographing while other actions are ignored as ‘no big deal,'” Peyton said.

To explain what a culture of consent looks like, Peyton told us about FRIES, which is the framework for consenting to intimate touching adopted by the Intimacy Directors and Coordinators of North America based on work by Planned Parenthood.

- Consent must be freely given, meaning that no one is allowed to pressure, force, or manipulate someone into intimacy. According to Peyton, “When you order your meal, you get to decide if you want some fries—no one can make you eat them.” In the theatre world, this means a director cannot force anyone to kiss, and if an actor doesn’t want to kiss someone, Peyton choreographs a mock kiss, or something that looks like a kiss but isn’t.

- Consent is reversible, meaning that someone may withdraw their consent at any time. “Even after you order, you can change your mind and not eat the fries.” This still applies even if you’ve given consent before, and the only thing an actor must do is inform the director, their intimacy partner, and the intimacy coordinator of their decision before going onstage.

- Consent is informed, meaning that the director clearly states beforehand when a part will require intimacy and when that intimacy will start being part of rehearsals. “Before you can choose if you want fries or not, you need to know when lunchtime is and where you are going to lunch.” If intimacy isn’t previously arranged or discussed, one always has the right to walk away from the situation.

- Consent should be enthusiastic, meaning that one should be satisfied with their decision to give consent. “You need to be happy with your fries—otherwise, something is wrong.” Creating enthusiasm around consent looks like making sure everyone involved feels emotionally supported and rewarded by the intimacy done.

- Consent must be specific, meaning that there can be no uncertainties as to what intimacy will happen. “You only get what you order—just because you want fries doesn’t mean you want a brownie.” Similarly, saying yes to one intimate act doesn’t mean one is saying yes to others (e.g., if an actor gives consent to a kiss on the cheek, that doesn’t mean they’ve given consent to a kiss on the lips).

“It is critically important to have a culture of consent not just in our theatre program but in all of Frederick,” Peyton said. “It’s about respect. You can’t have any trust, and you can’t make good art if you don’t feel safe or respected.”

Patrisa McHone • May 12, 2023 at 7:15 pm

Very well written and informative. Thank you for sharing this article.