The Rocky Mountain Irish

St. Patrick’s Day is not just a day to wear green–it has direct connections to Colorado history

Sophomore Mikayla Johnson and Payton Shelley pose in the their Irish garb for St. Patrick’s Day 2022. “I like delicious food and the color green, so I love St. Patrick’s Day!” Yet when asked, she (like lots of students) had no idea why St. Patrick’s Day is celebrated. The answer doesn’t have to do with just Irish pride, but also Colorado pride.

March 17, 2022

Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated annually on March 17 every year. The holiday is simple: it celebrates the legend of Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland who drove all the snakes off the island and died on March 17, 461. For over a millennium, this national apostle of Ireland became synonymous with Irish pride, and his symbol the shamrock (a common plant that St. Patrick used to explain the nature of the Christian trinity to native Celts) has become a sign of luck. We celebrate each year by holding parades, helping our younger siblings build leprechaun traps, and wearing green (and pinching those who aren’t).

All of this is mostly common knowledge–even kindergartners know that St. Patrick’s Day means wearing green, pots of gold, and Ireland. But why do we here in Colorado make such a big deal about an Irish holiday? The truth is that America celebrates St. Patrick’s Day for a different reason: Irish heritage. While 11% of the US population has at least one Irish ancestor in their family tree, those with Irish heritage weren’t always popular. In fact, the story of Irish immigrants in Colorado is an inspirational story of survival.

It all started with the Irish Potato Famine of 1845. A fungus killed most of the potato crop in Ireland, which was the main food people ate. Without a good source of food, the Irish needed to move away to survive. While most people would assume that they would go to England or Scotland, as both are close to Ireland and speak the same language, they did not. After the Act of Union in 1801, Ireland became part of the United Kingdom, but England treated the Irish and Scottish as second-class citizens. One of the first things the British brought over to Ireland was their laws against Catholics, as England embraced the Anglican Church. Unfortunately, most of Ireland was (like St. Patrick himself) Catholic, and the population suffered because of this discrimination. Irish mayors were replaced by English-born mayors, and Catholics had their property taken away.

Going back to the famine: by the time 1845 rolled around, the Irish really hated Britain but stayed in Ireland because it was easier than moving away. Then there was no food with the famine, and thousands of Irish families got that final push to convince them to leave. Most of these refugees fleeing hunger and oppression went to America, as the country spoke English and also escaped British oppression.

While the Irish thought they would be welcomed by Americans, they found themselves shunned again as second-class citizens. Papers unfairly depicted the Irish immigrants as lazy, violent drunks, and so many Irishmen were arrested without cause that a police transport earned the nickname “Paddy wagon” (for St. Paddy, or St. Patrick). Even Irishmen with wealth discovered that they had to work as servants or open their businesses far from the city centers.

Fortunately, the 1800s was a time when America was expanding West into new frontiers. While about half of the Irish population settled in major cities like New York City and Boston, the rest went to settle new areas of America in Appalachia and the far West. With the Treaty of Fort Laramie, Colorado was added to the American territories in 1851, and the Colorado Gold Rush of 1858 brought lots of workers to Colorado, especially the Irish.

Unlike the major East Coast cities, the Irish found a lack of discrimination in Colorado. While many stores in New York have signs that said “Irish Need Not Apply,” every hardworking man and woman had a place in the Rocky Mountain mining camps. When Denver was founded in 1858, several businesses were founded by Irishmen. When silver was discovered in Leadville, the town was founded and populated almost exclusively by the Irish. Leadville, which was known as “Little Ireland,” had more Irish immigrants than any other place west of the Mississippi. The Irish influence in Leadville made it a hotspot for the battle between unionization and corporate control that led to events like the Coal War and Ludlow Massacre.

When the Leadville mines went bust, most of the town’s Irish population moved to Irish-friendly Denver and then started settling in Northern Colorado. While Frederick, Firestone, and Dacono were all founded by Italian-American settlers, many of the miners that called Frederick home were Irish. The Irish got along well with the Italians, as both groups were Catholic. Meanwhile, Denver solidified its identity as a city with some Irish roots by electing the city’s first Irish mayor Robert Morris, who held the city’s first St. Patrick’s Day parade in 1882.

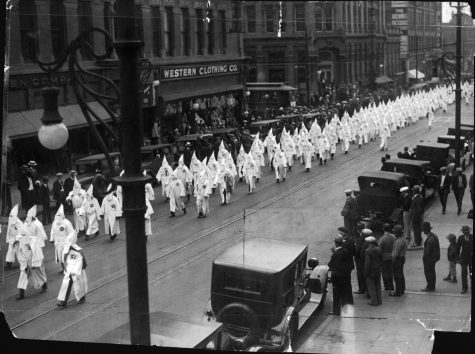

However, the tide soon turned for Irish immigrants in Colorado during the Gilded Age of the late 1800s. An anti-Catholic political party called the Know-Nothing Party was gathering influence all across the United States, and since Denver had an Irish Catholic mayor, it was targeted by these groups. “Orange societies” like the American Protective Association were founded in Denver and started growing in number. In 1900, they made their first political demonstration by flying an orange flag over the Colorado Capitol building on St. Patrick’s Day. More anti-Irish demonstrations followed each year, as the Orange societies had new allies: the Ku Klux Klan.

In addition to being racist and antisemitic, the Ku Klux Klan that emerged after the Civil War was also against Catholics and immigrants, making the Irish a target of their group. While the KKK was mainly involved in terrorism and lynching in the Southern states in the nineteenth century, the Klan started spreading west at the turn of the century. At the height of the Klan’s power in Colorado, Klan members controlled the state legislature and Denver mayor Benjamin Stapleton, who ended St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in the city. By 1924, there were Klaverns of the Klan in every Colorado county, with the largest in Longmont. Given Longmont’s proximity to Frederick, Irish-Americans in the Tri-Towns started hiding their roots and their religion for fear of persecution.

Fortunately, these dark times started to fade by the 1930s as Congress passed laws against the Klan and other groups promoting racial and religious terrorism. Over the next couple of decades, Irish pride began to grow slowly until William Henry McNichols Jr. was made Denver’s mayor in 1968. A proud descendent of Irish immigrants, McNichols brought back Denver’s St. Patrick’s Day parade and made wearing green on St. Patrick’s Day popular again. It helped that McNichols was extremely popular for helping create the Denver Performing Arts Center, The Colorado Art Museum, and the 16th Street Mall.

Decades later, our school is full of green shirts and light-up shamrocks. It’s a fun day to dress up and have fun talking in accents, but we should never forget how Irish immigrants shaped our community to be the wonderful place that it is.