We’re Often Blind to Colorblind Students

Colorblindness is more common than most people think--and it affects how students learn

February 28, 2022

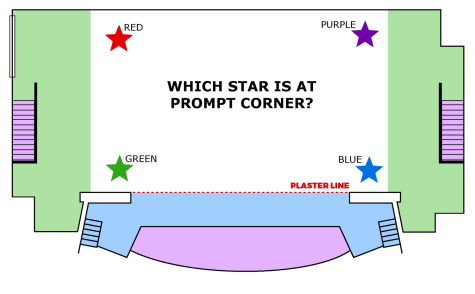

Look at the drawing above. Study it closely.

Do you see the green line?

If you can’t, you may be one of the one in twelve men who are colorblind.

According to Healthline.com, 9% of the global population has some form of colorblindness, with men more likely to be colorblind than women (1 in 200 women are colorblind). This makes the affliction as common as ADHD and nearly as common as diabetes. A person is more likely to be born with colorblindness than blue eyes or green eyes. So why are there lots of public awareness campaigns around ADHD and diabetes, while colorblindness is not as often discussed? More troubling, while everyone knows if they have blue or green eyes, not everyone knows that they are colorblind, which can lead to difficulties both in and out of the classroom.

Colorblindness at a Glance

To see colors, our eyes have three types of “cone cells”: red, green, and blue. Colorblindness occurs when these cells are damaged, malformed, or are not read correctly by the brain. When one of these three colors is missing, it affects eyesight on a whole. For example, some people with colorblindness mix up the colors red and green, as they look the same to them–this is an indication of protanopia (damage to red cones), deuteranopia (damage to green cones), or tritanopia (damage to the blue cones). Some people even only see the world in one color because they only have one kind of cone (monochromia) or lack all pigment in their cones and see no color at all (achromatopsia).

Colorblindness can also occur from tetrachromacy, a condition that happens in 12% of women where a fourth type of light-absorbing cone is found in the eye; this gives these women “super color vision” that allows them to see more colors and tones than the rest of the human population. This expansion of colors is considered a type of colorblindness as these women similarly do not see color the same way as the average person.

Colorblindness is often the result of a genetic condition and is present with a person from birth. This is why so many people do not know they are colorblind–the different shades they see are normal for them as they cannot know the difference that the average eye sees. While most people who suffer from colorblindness are born with the condition, colorblindness may also develop because of age. For example, more blue-yellow blindness is more likely to happen with aging. Other colorblindness may develop from alcohol consumption affecting the health of the eyes.

Less Color, More Problems

Being colorblind can affect a lot more than just driving, it can affect your whole future—such as jobs. Sophomore Jake Anderson, who is afflicted with red-green colorblindness, said “I do [automotive] races in my spare time, and green lights aren’t actually green for me, so it makes life a little harder.”

Certain jobs will not allow a person to work for them if they can’t see colors correctly. Chemical, electrical, and mechanical engineers all require color coordination because a lot of wiring and electronic parts like resistors are color-coded. Same scenario with an air pilot, as they have to distinguish certain colors and identify signals. Colorblindness similarly limits certain individuals from some types of military service (like the Air Force) while some specialty jobs actively seek people with certain types of colorblindness that allow them to see camouflaged soldiers easier. Those wanting to be doctors may be limited by colorblindness as they need to see color to treat and diagnose, while an aspiring police officer may be unable to describe a crime scene or what someone was wearing. A graphic designer, web designer, chef, interior decorator, painter– all of these jobs require precision in choosing colors and it can be hard if not impossible to achieve success in those fields whilst having colorblindness.

While student futures could clearly be impacted by colorblindness, most teachers feel it isn’t an issue in their classes. Mrs. Melissa Calderon, an art teacher at Frederick, told us that it wasn’t an issue in art, as”we can do adaptive stuff. There’s a lot of famous artists that are colorblind.”

This is true: Claude Monet suffered from tritanopia late in life, and because he couldn’t see shades of blue, his paintings became more red and yellow. While he couldn’t see color like he used to, he still made beautiful art that hangs in museums today.

Ms. Megan LeSage, another art teacher, agreed: “I don’t think it necessarily affects students. Everyone experiences the world differently, and everyone is going to see it through their own unique perspective. I’ve heard people tell me they’re colorblind but it’s never been an issue.”

However, there is a wrinkle to this story: Monet had cataract surgery to alleviate his colorblindness, as he felt it limited his artistry. While he adapted to his condition–he labeled all his paints with the name of the color–he still felt that his colorblindness made his life harder. This is the common issue with colorblindness–so many students don’t know they are colorblind, and so many teachers either don’t ask if students can see color or feel that it’s not a big issue.

“It makes working onstage really difficult,” Mr. Brandon Coon said when we asked him about students with colorblindness. Mr. Coon teaches technical theatre at Frederick, and he openly discussed how past students with colorblindness have struggled in his classes.

“In theatre, color is communication. We use colored tape called spike tape to mark where things go onstage at certain points in a show, as technicians don’t talk when onstage to keep the audience from noticing them. If a student can’t differentiate the colors, they can move something where it shouldn’t be. At best, it will jar the audience out of the show when the lights come up and something’s not right. At worst, an actor could trip over set they weren’t expecting to be in their way and break their leg.”

While backstage theatre is known for being as black and dark as possible, Mr. Coon showed us how much color plays into theatre design, from paint to shades of makeup to spools of sewing thread. “Every color communicates a feeling to the audience, whether they realize it or not.” Mr. Coon said. “Red makes people think of anger, blue makes people think of sadness. A student with colorblindness can memorize a list of those connotations, but it gets complicated when we add light.”

While we think of light as white, stage light is often colored with sheets of plastic called gels. These lights are colored because they make a set seem more natural or because they set a mood. However, everything on stage also has color, and when two colors mix, it can create a new undesired color.

“We usually have blue light onstage to make it look like night. Let’s say an actor comes out in a bright red shirt. Guess what–the shirt is no longer red; it’s either brown or black depending on how dark the blue light is. This color mixing is vexing for students with normal eyesight–it was maddening for the students I’ve had who had colorblindness. They end up communicating the wrong messages to the audience than they intended.”

He told us that, in his experience, students with colorblindness would either get very frustrated, not speak up out of embarrassment, have others do I’ll their work, or quit their interest in lighting, painting, and other jobs that use color a lot and moved to jobs that seldom use color lie building and sound. “We make it work,” Mr. Coon said, “but I’ve had a handful of students who just gave up because it’s hard to see the world in a way that you can’t understand. I do what I can to help, but it can be difficult to make students reframe limitations as challenges when a show is in two days and it’s taking them an hour to figure out something a student without colorblindness could solve in five minutes.”

Making People See Colorblindness

So, what can be done to prevent colorblindness? Not much, really. There is still no cure for colorblindness: despite extensive testing among other species of animals where genetic colorblindness has been cured, none have been allowed to move onto human trials. There are lenses and glasses that can help aid certain types of colorblindness by increasing color contrast, but most are hundreds of dollars and may not work best for those with prescription glasses. If a person develops colorblindness due to a condition or disease, addressing the condition or illness can sometimes cure the colorblindness, though sometimes the damage to the eye and its nerves is permanent.

So if we cannot cure colorblindness, we need to make our school and community more colorblind-friendly. Now, we shouldn’t just make everything black and white and gray, but there are steps we could take as a school to make sure that students with colorblindness have the same access as others. Here are some ideas:

- Make handouts on white paper, not colored paper: The best way to help students with colorblindness is to increase color contrast so they can tell the difference between shades. The ultimate contrast is black on white, so making sure that students with colorblindness get black-and-white handouts instead of those on colored paper helps significantly.

- Change the screen setting: What if you run a paperless classroom? Students with colorblindness can still struggle with contrast on an iPad or a cell phone screen. To help them, show them how to go into their settings and change the color filter in their display or activate “Differentiate without colors,” which adds symbols to help someone navigate without needing to see color.

- Write in black or a dark color on a whiteboard instead of using light-colored markers: While using colored markers may make instructions easier to follow for most students, students with poor vision or colorblindness have difficulty telling light colors from the light whiteboard, especially if there is a glare. By sticking to black, dark blue, dark green, purple, and dark red colors. teachers can make sure their writing can be easily read by all students.

- Mark dark surfaces with light colors: By the same token, any darker surface should be marked off with a light color so students with colorblindness can see them. On the black stage of the auditorium, a music teacher should mark things with light-colored tape. Out on the field, a coach should mark the grass with white chalk instead of yellow or orange (which don’t always stand out against the green of the grass).

- Write out the names of colors if they are relevant to instruction: Teachers often use colors to simplify instruction–“Grab the blue book on my desk,” “Fill out the pink sheet,” “Click on the blue button that says send.” While coding is very helpful to the average student, it can be very challenging for a student with colorblindness. A simple solution is for teachers to label the color on the item whenever they can to help students who can’t differentiate the color but can differentiate the name.

- Make sure supplies are labeled with words, not just colors: Similarly, teachers should make sure that colored pencils, paints, markers, and other supplies that require different colors have the name of the color clearly written on them. Teachers should also (within reason) use whatever colors they would like and can differentiate–if they need to color a map for geography, they may not be able to see the difference between the blue water and green land, so allow them to color the land purple and the water yellow if it helps them see better.

- Film your class in black and white: If a teacher really wants to see if their classroom is colorblind-friendly, they should ask a teacher friend to record an entire class they teach on their iPad. That teacher can then watch the video and see how often they reference color and, with the application of a black-and-white filter, they can see what parts of their classroom are hard to navigate with monochromatic eyes.

- Make sure colorblindness is found and documented: The hardest part of colorblindness in students is, as I’ve discussed, that not all students with colorblindness know that they have the condition. While the annual school eye exams check vision, they do not necessarily look at colorblindness. So students should start by taking a simple online test to see if they may have a problem with their vision, like this one by EnChroma. While these tests are not the same as a medical diagnosis, they can indicate if a student should get their eyes checked out. If colorblindness is diagnosed, the student and their parent should have it documented by the school on a 504 plan so all teachers know and can help that student.

- Teach students about colorblindness: Finally, teachers can talk to their students about colorblindness as a condition and how we can help those we know who have colorblindness with everyday activities that involve color, like coordinating outfits or safety cooking meals. If a teacher does talk to their students, they should make sure not to call out any individuals who may have the condition and they should use person-first language (student with colorblindness, not colorblind student). By talking to students openly about their condition, we can make the school a place where students can be open about their condition and be more comfortable seeking help.