At the White House Tribal Nations Summit on December 9, outgoing President Joe Biden used his powers under the Antiquities Act to create the Carlisle Federal Indian Boarding School National Monument in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The monument carves away a couple of buildings and some grounds from the U.S. Army War College that just a little over a century ago was the Carlisle Inidian Industrial School. The housed not only 7,800 from 140 tribes but also tortured children, broke up families, and participated in genocide against the First Nations from 1879 to 1918.

As indicated by the name, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was one of hundreds of residential schools established after the Civil War by the federal government, which then took Native children from their families and essentially imprisoned them in the schools in order to “civilize” them—their term for rejecting the culture and language of their ancestors to instead adopt Anglo-Saxon protestanism. The schools often did this by force and would hurt or starve pupils that refused to comply, and not every child “educated” in these schools survived to childhood.

President Biden declared this national monument to fulfill his promise to the First Nations that he would do what he could to right the wrongs of the past. Under Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (who belongs to the Laguna Pueblo tribe), the Biden administration created the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in June 2021, which has the goals of researching the full impact the Federal Indian Boarding School (FIBS) system had on indigenous tribal communities and then using that research to shed light on that dark chapter of American history.

Taking its cue from the Biden administration, Colorado Governor Jared Polis signed HB24-1444 last May, a law that created the state’s own version of the FIBS Initiative. The bill will give the nonprofit History Colorado $1 million for each of the next three years to research “the physical abuse and deaths that occurred at federal Indian boarding schools in Colorado,” create a public report, and make a list of recommendations on how the state should own up to and atone for its past. And with the new year started and the project budget paid, History Colorado is currently finalizing a panel of 10 FIBS survivors to visit former FIBS sites, interview other survivors, and gather everything the state needs for their report.

Colorado’s Involvement

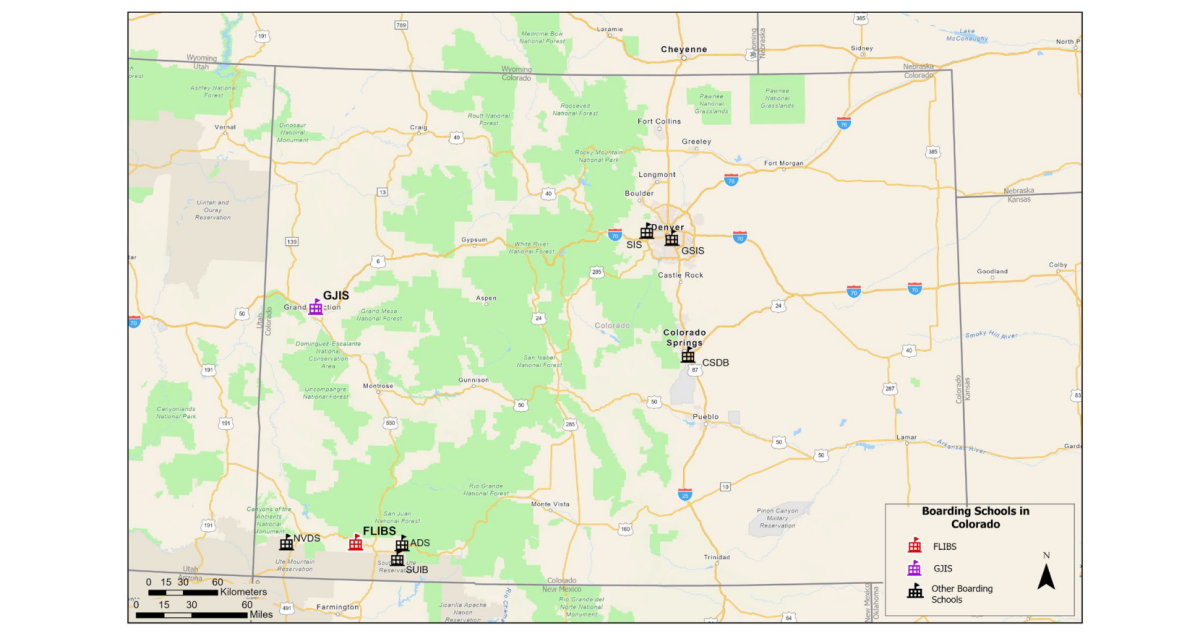

While these facilities were spread all across America, including Alaska and Hawaii, Colorado had seven sites managed by the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs:

- The Grand Junction Indian Boarding School (later the Teller Institute), 1888—1911

- The Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School, 1892—1909

- The Ignacio Day School (on Ute reservation), 1884—1890

- The Southern Ute Indian Boarding School (on Ute reservation), 1912—unknown

- The Allen Day School, Bayfield, 1912—unknown

- Navajo Springs Day School (on Ute reservation), 1912—unknown

- Towaoc Day School (on Ute reservation), 1916—unknown

In addition to these federal sites were two other boarding schools that took indiginous children: one run by the state of Colroado (The State Industrial School for Boys in Golden, 1881—1968) and one run by the Catholic Church (The Good Shepherd Industrial School for Girls in Denver, 1887—1961). These weren’t Indian Schools per se but schools for “delinquent and orphaned children” of all races. Still, these weren’t the best places for children either, as they were run like military schools, harbored abuse, and made students work without pay for school-owned businesses.

Additionally, a handful of Native children were sent to the Colorado School of the Deaf and Blind (CSDB) in Colorado Springs. Though the government forced these kids off-reservation to a strange place where they didn’t know the language, CSDB was for all intents and purposes just a regular school—unlike Indian or industrial schools, the students weren’t beaten, they could keep their Native names, and they would return to their parents and the reservation every summer.

However, Colorado’s role in the FIBS system is bigger than the handful of schools. The FIBS project was the brainchild of Henry Moore Teller, a Colorado senator that became Chester A. Arthur’s Interior Secretary (and thus the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs) in 1882. After his friend Nathaniel Meeker was killed by the Utes during the Meeker Incident of 1879, Teller advocated for a re-education system that would “civilize” First Nations, and he found a model for his ideal in Richard Henry Pratt’s Carlisle Institute and its “kill the Indian but save the man” philosophy. This philosophy became policy when Teller became Interior Secretary, and the whole FIBS situation would arguably have never spread across the country if not for him.

How the Schools Worked

Here’s how the federal government wanted the boarding schools in Colorado to work: children from ages 6 to 12 would go to an on-reservation day school staffed by white teachers only using English and then return to their families at night. After a child turned 12, they were sent to the Teller Institute or Fort Lewis for “high school,” where they lived with no contact with their families. While most would then either return to the reservation or integrate into lower-class American society, Teller hoped that some would attend “the agricultural college” that later became CSU.

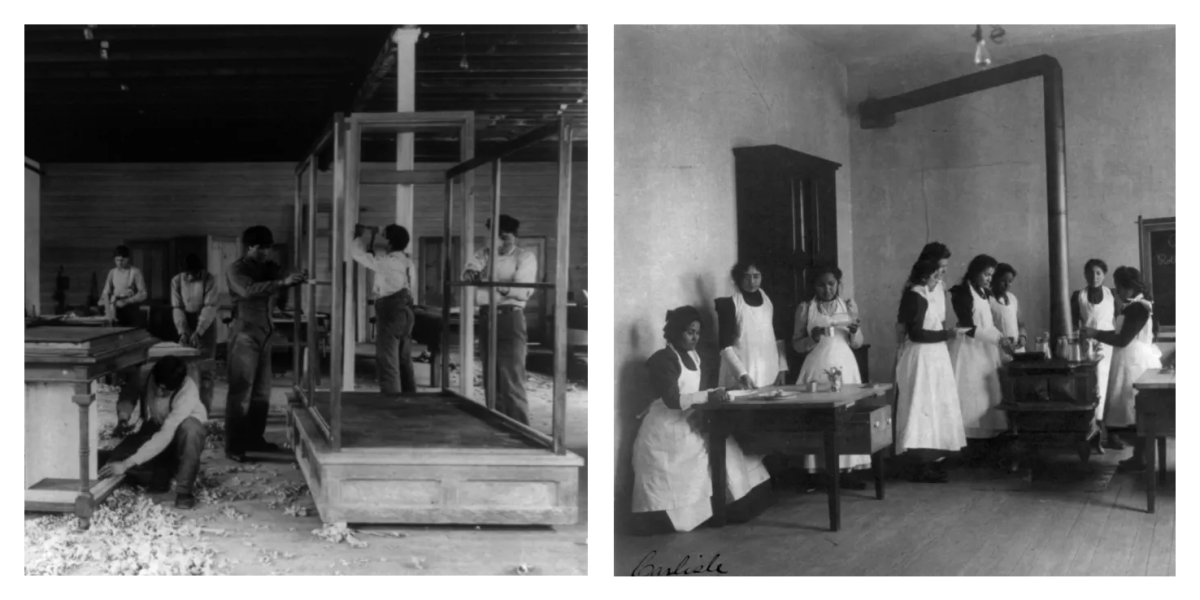

If a student was exceptionally bright or talented, they would be shipped off to the Carlisle Institute in Pennsylvania for a “real” education with reading, math, and science—the education at the state schools focused only on how to speak English and how to conduct agricultural or domestic labor. If a student ran away, they would be sent to one of the two state Industrial schools after they were caught.

However, this “ideal” system did not work in reality, as it took decades to establish most of the day schools because white teachers were reluctant to teach on a reservation—this issue was so bad that the Allen Day School opened not on the reservation but adjacent to it in the town of Bayfield. Until these schools were established, the vast number of 6-to-12-year-old of the tribe were sent to learn and live at the Teller Institute or Fort Lewis.

In 1912, Colorado finally returned all Native students (execpt, obviously, those attending the Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind) to the Ute reservation by closing closing the Teller Institute and opening the Southern Ute Indian Boarding School. While these schools were still run by the federal government and were almost exactly like Teller and Fort Lewis, all these reservation schools were turned over to the Ute tribes to manage sometime before 1934—the exact date is unknown because Indian schools intentionally kept terrible records.

What These Schools Were Like

Why did these schools intentionally keep such terrible records? Well, a lot of horrible abuse and neglect happened at these schools that nobody wanted to record. All cultural touchstones of the tribe, from the long hair traditionally worn by boys to their traditional clothing, were taken away. Only English was to be spoken—any child that spoke their tribal tongue would be punished with a beating, a lashing, starvation, or isolation. This meant that all children were given English names by the headmaster, names they didn’t even get to choose.

With all their old clothing and possessions taken away upon arrival, students were given uniforms to wear that were made onsite by the female sewing students. In fact, almost everything given to the Native students came from their own labor. Male students would farm the food for the student body and the women would cook and serve that food—this led to little food and poor nutrition throughout the schools, as novices were being forced to produce food. If the school needed construction or plumbing repairs, from roof to fencing, the male students would have to figure out how to fix it while the female students were expected to keep the school clean. Teller and Fort Lewis even had leather shops where students would make their own shoes.

Unlike the mission and military based systems popular in other states, none of theses schools (except Good Shepherd, which was run by nuns) forced children to convert to Christianity. However, conversion was encouraged and teachers would often use biblical references in lessons to nudge pupils into reading the bible. Students were also not allowed to worship in their traditional way.

If any student broke the rules, the most common punishment was physical harm despite corporal punishment being banned in federal schools in 1893. Physical abuse include being slapped in the face, spanked, kicked, and punched, though worse may have happened off the record. What occured more often than physical strikes was abuse occuring from neglect which wasn’t specifically illegal: student would have their food withheld, be made to sleep outside in the cold, or isolated from others for an extended time. Some torture was psychological, as students were occasionally threatened with jail or abandonment in the woods. Other abuse was sexual: for example, the Denver Post revealed in 1903 that Fort Lewis’s Superintendent Thomas Breen had subjected girls and young women to sexual abuse for years.

Why These Schools Got So Bad

While the 1903 investigation was shocking, most of these abuses were ignored at the time. One major reason that abuse wasn’t reported is because teachers were so hard to find for these schools that they were allowed to do pretty much whatever they wanted. Corporal punishments such as spankings were also common in regular schools up until the 1970s—Colorado only banned it from schools in 2023. More than anything else, these abuses were allowed to occur because of widespread racism against First Nations members. After all, the problems of Native tribes were routinely ignored by authorities, injured students were almost never taken to a public hospital (as there was an on-campus hospital), and none of the students had parents that would come to their defense because their parents had no idea what was happening.

Ultimately, the widespread abuse and neglect of injured or sick students resulted in a lot of student deaths. How many? We have no idea. As mentioned, schools kept bad records for this exact reason and were responsible for reporting their own fatality numbers (with the only exception being the Colorado School for the Deaf and Blind, which kept impecable records and had only two Native students die from cerebrospinal meningitis in 1896).

The deaths currently known that occured at these schools are the result of either survivor testimony or investigations by newspapers at the time. For example, an 1896 report from Fort Lewis claimed there were no student deaths that year while the local press identified five deaths. That same year, a fire burned down three buildings at Fort Lewis yet no injuries were reported, which seems highly unlikely. If a superintendent was caught lying about their records, they wrote it off as a problem because their school was overcapacity (as Indian schools almost always were).

The body of a dead student wasn’t sent back to their family. A hole was dug and the corpse was buried on-campus with no gravemarker. And who dug those graves? That’s right—students.

What’s Being Done about It Now

This lack of specificity and accountability is what the new Colorado commission will research. Over the next three years, they will interview as many living survivors as they can, collect any documents that exist, and explore the sites of these schools to the best of their ability. These researchers want an as close as possible accurate accounting of how many students were at each school, who they were, what tribe they came from, and how many died.

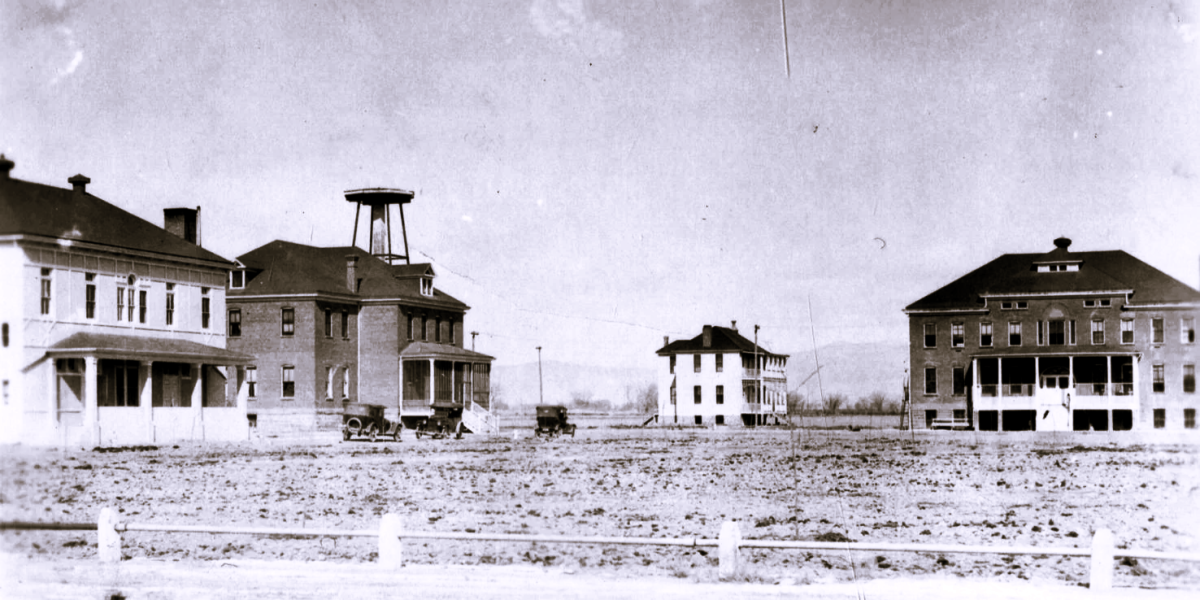

There will be issues with this because, while a 2022 bill ensures their access to every site, the buildings and grounds of some of these old schools have radically changed because they’ve been in use by other groups after folding as a school. Fort Lewis College is built on top of the former Fort Lewis Indian Boarding School, so there are likely remains under recently constructed buildings, and the Teller Institute was most recently used as a care center for adults with severe disabilities.

Once a more accurate picture of what exactly happened at the Colorado Indian Boarding Schools is created, the commission will then make recommendations on what should be done with the still-existing facilities (torn down, turned into a museum, etc.) and what the state in its official capacity needs to do to make amends for the wrongdoing in the past. This could include execvating the dead and reburying them on tribal land, monetary reparations to the affected families, creating a monument or other memorial, or changing the names of places in the state to remove commeration to those that perpetrated these crimes like Meeker and Teller. The last of these happened in 2023 when Mt. Evans became Mt. Blue Sky due to John Evans’ involvement in the Sand Creek Massacre and in 2020 when the Stapleton neighborhood became Central Park due to Benjamin Stapleton’s involvement with the Ku Klux Klan.