Si quieres leer esta historia en espanol, haz clic aqui.

If you didn’t come home one day, what would happen? Likely, your parents would contact the police, a search would be called, and an Amber alert would go out to phones and roadway signs announcing that you are missing. This is the general expectation for what needs to happen when someone in the community goes missing: everybody tries to find them.

This doesn’t happen with members of First Nations communities.

The epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous Americans has been a long hidden tragedy in the United States. For generations, police have been more likely to neglect a case involving an Indigenous person than any other case. This injustice has left families without closure and has deep roots in colonization and inequality. After centuries, Indigenous communities have been joined by justice advocates in demanding that the United States do something about this epidemic.

The Horrifying History of Natives in America

Before we look at the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous people right now, we need to look at what Native Americans have been through throughout history. Native Americans had a vibrant culture that was suppressed by European colonizers from Alaska to Argentina. From the time of Columbus to the Civil War, Indigenous Americans were forced off their homelands, kidnapped and sold as slaves, and brutally killed if they fought back. After slavery was abolished, government efforts shifted to confining Natives to reservations on unwanted land or to assimilate Natives into mainstream American culture–the 1869 “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” act really says it all.

This act called for forcefully taking Native American children away from their homes and putting them in government-funded boarding schools that forcefully converted them to Christianity to make them “normal.” It’s not known how many total Native American children were taken, but it’s estimated that 20,000 children were in these boarding schools by 1925. These “Schools of the Americas” punished the children for speaking their native language or practicing any aspect of their culture. Children suffered physical, sexual, and mental abuse at the hands of these schools, and if the schools were “successful,” that child would grow up to embrace mainstream American culture and never visit their family or tribe again.

While the lessons taught at these schools were wicked, the lesson they taught the Native communities was worse: we can take your children, you will never see them again, and there isn’t anything you can do about it. Most families would never know if their children even survived school, as many didn’t. The children that perished from the abuse didn’t even get a proper burial: they were just tossed in a big hole with other dead bodies and were not memorialized in any way. Even the children who survived these schools wonder what happened to some of their friends or siblings, as even they have no closure if they are alive or dead. These schools sent a clear message: your Native lives don’t matter to us.

The End of Empathy

Native boarding schools were just one link in a chain of discrimination going back to colonization. Europeans moving to North America needed land to live on and to farm, so they would either kick Natives living in that area out or make unfair treaties with them (which were eventually broken by colonizers anyway). Natives resisted, but Europeans outpowered them with their larger numbers, firearms, and horses.

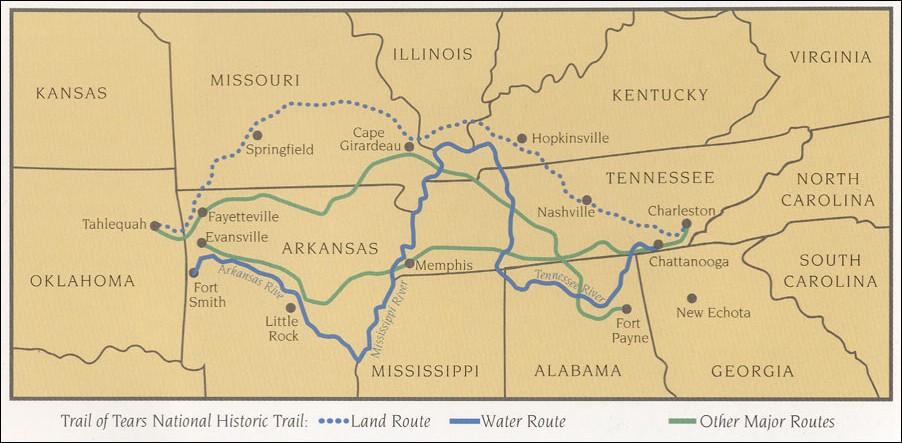

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed into law what became known as the Indian Removal Act. The Indian Removal Act outlined that Natives were granted lands in “Indian territory” in exchange for their lands within existing state borders. Some tribes went along with the act, but most tried to fight it. In the end, the American military won out, and about 60,000 people of those tribes were forcibly moved from their homes and forced to relocate to “Indian territory.”

This forced relocation became known as the Trail of Tears. Approximately 10,000 died during the march from starvation and disease as they slogged through Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas to their eventual destination of Oklahoma. This trail is also one of the many genocidal actions taken against Native Americans and was triggered when gold was discovered on Indigenous lands–gold that Jackson wanted for the US Government. In a stunning example of presidential overreach, Jackson ignored a Supreme Court decision upholding Native rights to their own lands and relocated the tribes anyway.

The Trail of Tears created a precedent for the US Government that they could treat First Nations like second-class citizens. Those who died on the trail were hastily buried and, while mourned by their friends and families, were ignored by the soldiers. There were no repercussions or concerns when someone went missing or died. This also became true of future removals that happened under western expansion. The modern practice of ignoring when Indigenous people go missing or die became part of military and later police procedures comes directly from this legacy.

The Modern Crisis in Native Communities

While removal to reservations and boarding schools doesn’t currently happen, those events still linger on in how Native Americans are treated when they disappear or die. It’s estimated that nearly 6,000 Natives are missing persons, and of the 28,845 children that go missing, 294 are Natives. These numbers are probably underreported, however, as only 47 of the 573 tribes in the US share their crime data with the government. While only 13% of Indigenous Americans live on reservations, these communities are the best sources of information but do not trust the government because of past injustices.

This overrepresentation in crime is likely that this is the result of racism against Native culture, but it’s also likely motivated by the fact that perpetrators know they can get away with kidnapping and murder and that their crime won’t be investigated. This explains why 40% of sex trafficking victims are Natives–it’s easy to victimize someone knowing that it’s unlikely that the crime will be investigated. Native women specifically suffer from injustice more than Native men: 56% of Native women experience sexual assault (twice as likely as all other women), and murder is the third leading cause of death for Native women (three times as likely as all other women).

Since police have historically been resistant to helping Natives, an organization called Murdered and Missing Indigenous Relatives (MMIR) stands to bring these people to justice. MMIR strives to bring missing indigenous people home through awareness campaigns for the public and pressure campaigns on police forces. On their website, they list missing or murdered Indigenous people, whether or not they have been found, and if the case has been solved. This organization is usually represented by a bloody hand over the mouth to represent the First Nations being silenced and not being able to speak.

Breaking the Cycle

As the number of missing and murdered Indigenous people is on the rise, the Frederick community can help by spreading awareness of this issue. Colorado is one of the most proactive states when it comes to Native equality, as efforts from MMIR have resulted in the Colorado Bureau of Investigations opening the Office of the Liaison for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives (OMMIR) and the Missing Indigenous Person Alert Act of 2022. Now an Indigenous person that is confirmed missing will get the same treatment as a missing child: text messages sent out, TV and radio notifications, road sign warnings, and a full police search.

Still, these measures only do so much. According to MMIR, there are currently 14 missing Indigenous Coloradans (four of whom are children) and 29 unsolved murders of Indigenous Coloradans. This compares to the 5,712 cases nationwide. If you want to help, you can donate to MMIR Colorado, support efforts to get more police training around how to handle crimes against Indigenous people responsibly, and celebrate the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Relatives on May 5.

Personally, you can also research more about the history of the mistreatment of Indigenous Americans and resolve to do better yourself. Support those with Native heritage in the school community and don’t make fun of them. We need to come together as a community and try to prevent further injustices against Indigenous people. If you hear or see anything, report it.